after credits: wake up dead man (a knives out mystery) takes a dig at substack

This is just the beginning of my London Film Festival marathon – still have eleven days and twenty-something films to go. God help my eyeballs.

There’s an overpowering feeling that hits when you walk into Picturehouse Central during the London Film Festival. The walls hum. People clutch their printed schedules like treasure maps. Someone’s arguing about whether to skip their 6pm for the standby line at the 8:45. I inhale the stale popcorn air and think, this is home for the next two weeks. Screen 1’s red seats have cradled my spine through more screenings than I care to admit. Its brutalist stairwell echoes with the footsteps of critics pretending they’re not racing to claim the best seats. Press and Industry screenings began a few days before the festival officially opened—I caught The Secret Agent and Weightless in rooms where people still whisper during trailers, which I respect.

Yesterday was Opening Night. I caught Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery at 8:00 in the morning (the commitment!), Daniel Craig doing his Benoit Blanc thing, and me sitting there wondering if I’ve already forgotten how to have hobbies that don’t involve sitting in the dark. I have thoughts—oh, do I have thoughts—about this movie and everything else I’ve seen so far, which I’ll get into after the paywall for my paid supporters. But first, I need to show you something that I think captures the entire experience of being press at this festival.

Because here’s the thing: LFF isn’t just about watching movies. It’s about the logistics. The planning. The spreadsheet I definitely did not make at 6.58am mapping out toilet times between screenings. And most importantly, it’s about the booking system that either makes you feel like a god or reduces you to tears. I’m talking about the portal where we select our screenings—a beautiful, terrifying interface that’s basically film festival Hunger Games.

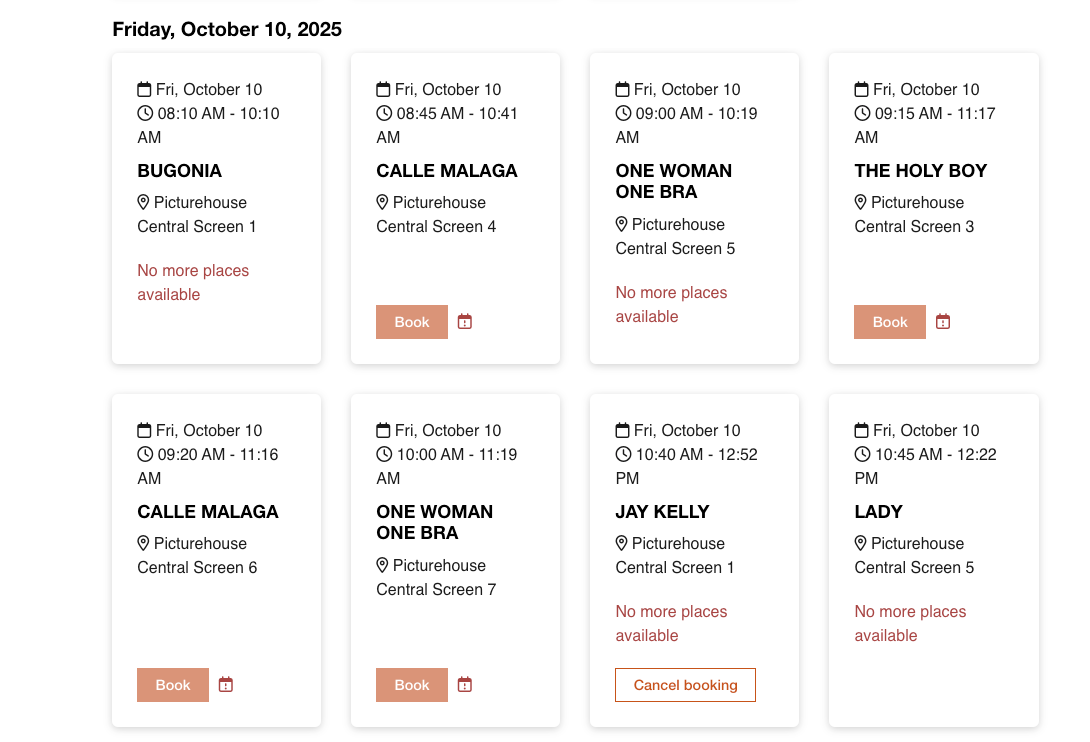

So let me show you a screenshot of the booking calendar. And I think once you see it, you’ll understand why I’ve been communicating exclusively in nods and grunts to my friends, why I’ve been living off Pret sandwiches and spite, and why my screen time report this week will look like a cry for help.

So here’s how this works. The booking system opens at 8am, two days before each screening. You’re meant to wake up, open the Eventmaker app, and calmly select your films like you’re ordering coffee. What actually happens is you’re there at 7:58am, phone in one hand, laptop open as backup, refreshing the page like you’re trying to get Glastonbury tickets. But I promise you, there’s a Lord of the Flies energy to this whole thing. Miss too many pre-booked screenings and they’ll suspend your pass. They’re tracking this. Someone at the BFI has a spreadsheet with your name on it and they know you skipped that 9am documentary about Bulgarian beekeeping because you were hungover. Film festivals really said we’re going to make you feel like you’re being monitored by a disappointed parent and then charge you for the privilege.

And yet—look at this. This is what Friday looks like. BUGONIA at 8:10am. CALLE MALAGA at 8:45am. ONE WOMAN ONE BRA at 9:00am. THE HOLY BOY at 9:15am. All of these screenings happening at the same time, obviously, because film festivals hate you and want you to suffer. You’re constantly doing this grim calculus: Can I sprint from Screen 1 to Screen 4 in five minutes? Will I have time to pee? Should I just accept I’m going to miss the first ten minutes of something? There’s a standby queue if you don’t get a booking, which means showing up early and hoping someone cancels or, more likely, that a bunch of people just don’t show up.

I’ve stood in standby lines where I’ve genuinely questioned went into mental breakdowns. But also, I’d do it again tomorrow because Bugonia filled out in zero time 😭 (Lanthimos, my boy I’ll do my best!!)

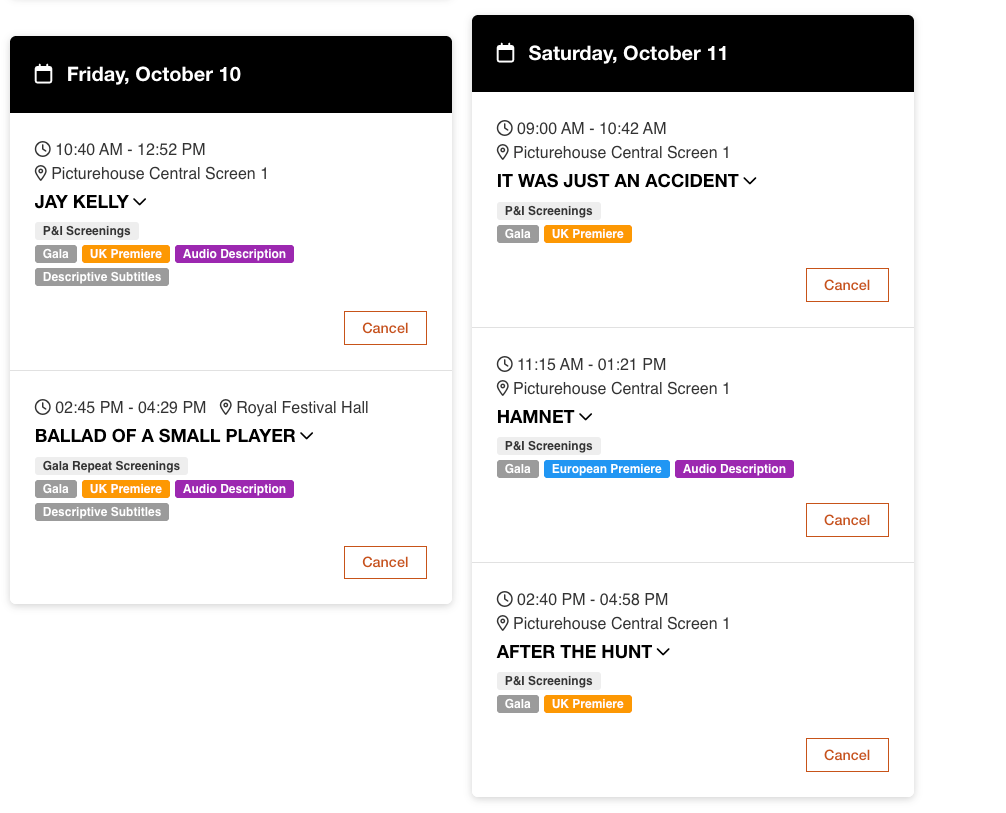

Tomorrow morning I’m seeing Noah Baumbach’s Jay Kelly, Clooney playing an aging actor getting a lifetime achievement award with Sandler and Dern hovering nearby. Baumbach loves making films about people who’ve achieved everything they wanted and are miserable about it, so I’m assuming this will be sad in ways I haven’t prepared for. Then in the evening it’s Ballad Of A Small Prayer. Colin Farrell gambling in Macau, Tilda Swinton doing whatever Tilda Swinton does when directors let her be ethereal.

Saturday is Jafar Panahi at 9am. It Was Just An Accident won the Palme d’Or—it’s about a traffic accident in Iran that very quickly stops being about the traffic accident. Panahi’s films have a way of making you feel complicit just for watching them so naturally, I can’t WAIT. Then Chloé Zhao’s Hamnet, where Jessie Buckley is Shakespeare’s wife watching her husband turn their dead child into Hamlet. I’m really curious what she does with grief that’s already been mythologized for 400 years. Ending the day with Guadagnino’s After The Hunt—Julia Roberts as a professor, something about a sexual assault accusation on campus. People keep saying Roberts gives a career-best performance, which is a phrase that shows up in press notes so often it’s lost meaning, but Guadagnino has this ability to make actors unravel on screen in ways that feel uncomfortably intimate so I think we may have a hit there.

I had plans these next 2 weeks. Cancelled them. Someone texted about weekend drinks and I replied “I’m at the festival” like that explains why I can’t meet for one (1) pint. But festivals do this thing where regular life, going to dinner, having conversations that aren’t about movies you just watched, starts feeling impossibly slow, like you’re moving through honey while everyone else gets to sprint. Roger Ebert saw 500 films a year and I think about that standing in the Picturehouse queue staring at the same sandwich I’ve eaten three days in a row, wondering if he also lived like this or if he had, like, friends and hobbies.

Anyway. Here’s what I actually thought about WAKE UP DEAD MAN, THE SECRET AGENT, and WEIGHTLESS.

WAKE UP DEAD MAN: A KNIVES OUT MYSTERY

I’m going to be very clear about this: Wake Up Dead Man is exquisite. It’s my favorite Knives Out by a significant margin, and I say that as someone who thought the first film was good and Glass Onion was fine if you squinted. Rian Johnson finally figured out what these movies should be—not just whodunits with celebrity cameos, but actual examinations of power structures that use the murder mystery format to say something. This one’s about religion, cults of personality, and how easily faith gets weaponized into control. Josh Brolin plays Monsignor Jefferson Wicks, a fire-and-brimstone priest who’s basically a cult leader in clerical robes, and the film doesn’t shy away from making the Trump parallels explicit. His congregation worships him. He’s magnetic and terrifying, and Brolin plays him like a man who knows exactly what he’s doing when he tells people God wants them to be afraid.

But this is Josh O’Connor’s movie. I’m going to say something that might sound hyperbolic but I mean it: This film solidified for me that Josh O’Connor is the best actor of his generation. He plays Father Jud Duplenticy, an ex-boxer turned priest who’s been sent to Wicks’ parish after punching out a deacon. O’Connor makes Jud feel like an actual person—not a type, not a symbol, but someone with a specific history and a specific way of moving through the world. He’s funny without trying to be funny. He’s sincere without being cloying. There’s a scene where he comforts a woman who just needs someone to listen, and it’s the most emotionally grounded moment in any Knives Out film. O’Connor carries the first third of the movie on his own before Daniel Craig even shows up, and by the time Benoit Blanc enters, you’re already fully invested in Jud’s story.

Craig’s back to being great here. He’s less showy than in GLASS ONION, more grounded, and his scenes with O’Connor crackle because they’re playing two people who fundamentally disagree about faith but respect each other anyway. Blanc’s an atheist who thinks religion is a con. Jud believes in redemption and grace. Neither one changes the other’s mind, but they find common ground in trying to solve a murder that looks like a miracle. It’s the kind of ideological sparring match Johnson’s good at writing when he’s not trying to be clever about it.

Glenn Close and Josh Brolin are scene-stealers in the way veteran actors are when they’re given material that lets them be weird. Close plays Martha Delacroix, a parishioner so devoted to Wicks she’s basically his enforcer, and she’s terrifying in that very specific Glenn Close way where you can’t tell if she’s going to hug you or stab you.

Andrew Scott plays Lee Ross, a sci-fi writer who’s “freed himself from the liberal hive mind” and now spends his time trying to escape “Substack hell”. (Yes, Rian Johnson put a dig at Substack in his murder mystery. Yes, I laughed. Yes, the guy who was sitting next to me turned to me to laugh as well after I introduced myself as “Substack writer”. Yes, all of you reading this on Substack should also find this funny.) Scott doesn’t have as much to do as I would’ve liked, but he makes the most of it. Same with Kerry Washington, Cailee Spaeny, and Daryl McCormack—they’re all good, but the film belongs to O’Connor and Craig.

The mystery itself is satisfying in that classic locked-room way. Johnson plays with the mechanics of the murder in ways that feel genuinely clever rather than overly convoluted. There are twists that work and twists that don’t, but the film earns its reveals because it’s actually about something. It’s about how power corrupts faith, how institutions protect abusers, how people choose belief over evidence because evidence is harder to live with. Johnson’s made a Knives Out movie that understands religion isn’t just a set of beliefs—it’s a system, and systems can be manipulated.

I genuinely didn’t want this movie to end. It’s 144 minutes and I would’ve watched another hour. That’s rare for me, especially with something this structurally dense. But Johnson’s finally made a Knives Out that feels like it matters beyond being a well-executed genre exercise. It’s smart, it’s funny, it’s deeply cynical about institutions while still believing individual people can be good. It’s everything I wanted GLASS ONION to be and wasn’t.

WEIGHTLESS

Sitting in a half-filled screening room watching Weightless, I kept thinking about how we never properly talk about teenage girls’ bodies. We moralize, we concern-troll, we pretend to protect but nobody wants to admit the jagged truth that Emilie Thalund’s debut puts on screen: teenage girls’ bodies are battlegrounds where adult anxieties wage war.

This film got under my skin. Not because it’s perfect—it isn’t—but because Thalund refuses to sand down the rough edges of her 15-year-old protagonist Lea (Marie Helweg Augustsen) as she navigates the suffocating environment of a Danish summer “health” camp. Let’s call it what it is: a weight loss camp where teenagers are taught their bodies need fixing.

I spent ages 13 through 26 locked in a toxic cycle with food (and I still often battle with it). While other girls collected charm bracelets, I collected eating disorders—restricting, binging, over-exercising, switching between them like seasonal wardrobes. I’d starve myself for days, then eat until I felt possessed, then run until my knees threatened to buckle. Watching Lea measure her portions with militaristic precision, I felt that old familiar knot in my stomach. The body remembers.

What elevates Thalund’s film beyond after-school-special territory is her refusal to frame Lea as simply a victim of diet culture. Instead, she gives us a protagonist bristling with contradictory wants: to shrink and to expand, to be invisible and to be seen, to be a good girl and to burn everything down. When Lea fixates on her camp counselor Rune (Joachim Fjelstrup), the film dives into murkier waters that American cinema wouldn’t dare touch. Their dynamic isn’t the predator/prey narrative we’re accustomed to—though make no mistake, the power imbalance is glaring—but something more insidious. Lea weaponizes her perceived undesirability, using it as both shield and spear in her interactions with this deeply mediocre man.

There’s a Nordic unflinchingness here that reminds me why I’ll always choose a Scandinavian film over Hollywood’s sanitized bullshit. Thalund doesn’t care if you’re comfortable. She’s not interested in redemption arcs or tidy moral lessons. The ambiguity she creates around her scenes with Rune, showing us Lea’s face rather than his actions, forces us to sit in the swampy middle ground where exploitation and agency mingle in ways we’d rather not acknowledge.

Augustsen’s performance is a revelation. Not in that showy child-actor way that makes you wonder about stage parents, but in her ability to communicate the tectonic shifts happening beneath Lea’s surface with just the slightest changes in posture and gaze. There’s a moment when she watches her thin roommate Sasha (Ella Paaske) flirt effortlessly with boys that contains a universe of envy, confusion, and determination. If we’re honest, we all remember cataloging these moments, studying the girls who seemed to instinctively understand the rules of a game nobody had bothered to explain to us.

The cinematography by Louise McLaughlin deserves special mention for capturing the paradoxical nature of these teenage bodies, how they can simultaneously appear massive and fragile, how they can feel like prisons and weapons. I left the screening feeling raw in ways I didn’t anticipate because Thalund managed to capture the particular texture of shame and desire that permeates adolescence. The way these feelings aren’t separate but braided together, each feeding the other in a loop that can take decades to untangle.

In a festival lineup stuffed with safer, glossier offerings, Weightless might not make many top-ten lists but I’ll take Thalund’s prickly, unresolved exploration of girlhood over another quirky coming-of-age story any day. This is cinema that acknowledges bodies as political terrain while never forgetting they’re also the only homes we have.

A SECRET AGENT

I wasn’t prepared for the flies. That’s the thing about Kleber Mendonça Filho’s “The Secret Agent” that keeps haunting me days after the screening – those damn flies buzzing around a corpse at a gas station while people just... go about their day. Nobody moves the body. Police show up not to investigate but to extract bribes from Wagner Moura’s character. It’s Brazil, 1977, under military dictatorship, and Filho refuses to shoot fascism in shadows. It happens in broad daylight, under a punishing sun, because why bother hiding when nobody can stop you?

Moura is so good in this I forgot he was acting. After watching him play Americans and Colombians and whatever Netflix needed him to be, seeing him back in Portuguese feels like catching up with a friend who finally dropped the persona they’d been using at work. He moves through Recife during Carnival as Marcelo, a technology expert returning home to find his son. The city feels alive in a way most “foreign” locations in Hollywood films never do – Filho was born there, and he shoots Recife like someone mapping the scars on a lover’s body, familiar with every imperfection.

The film runs 158 minutes and honestly could’ve gone another hour. Not because it’s slow – though it luxuriates in moments American thrillers would cut – but because it creates a world so textured I didn’t want to leave. Maybe that sounds weird for a film about life under a brutal regime? But Filho has this gift for finding pockets of defiance and joy in the worst circumstances. There’s a resistance commune run by a 70-year-old woman whose charisma burns through the screen. There’s Marcelo’s son, whose fascination with sharks becomes weirdly significant. There’s even this bonkers subplot about a hairy leg found inside a great white that transforms into urban legend. On paper, it sounds ridiculous. On screen, it makes perfect sense.

Political thrillers usually give us heroes who save democracy with speeches and shootouts. Filho gives us people just trying to survive while maintaining some scrap of dignity. Nobody’s hands stay clean. The film’s flash-forward ending (which I won’t ruin) doesn’t offer easy resolution – how could it? Brazil’s still wrestling with the ghosts of this era. That’s what separates The Secret Agent from something like Argo or even Munich. It’s not interested in making Americans feel better about other countries’ trauma. It’s about memory as resistance, about the stories nations tell themselves to justify forgetting.

Seeing this made me think about how rarely we get political films that trust the audience to think. Filho doesn’t spoon-feed the history or announce IMPORTANT THEMES with swelling strings. He drops you into 1977 and trusts you’ll figure it out, the same way you’d navigate a foreign city without Google Maps – by paying attention, by noticing details, by asking questions. Between the corpse flies and the yellow Beetle and Moura’s weary eyes, The Secret Agent has been living rent-free in my head all week. Catch it soon if you can get tickets. Some films just need a big screen and a dark room to work their magic.

I’m camped out at LFF for the next two weeks, so expect more dispatches from the trenches as I survive on coffee and adrenaline. My judgment gets borderline psychotic around day ten of festival coverage, so the reviews might get weird. Consider yourself warned.

Josh O'Connor – yes!!! All that stock I bought of his back in 2018 is going to the moon right now.

I've only snagged three LFF tickets this year but saw (and really loved) Sentimental Value last night at the RFH. Don't suppose you were there?