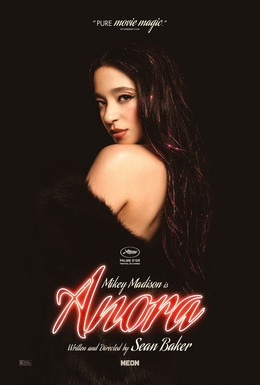

Two weeks ago, I watched a film about sex work, the Cinderella fantasy, and systemic oppression that had me cackling with laughter before crushing my soul into a fine powder - and this, my friends, is exactly how cinema should work. Sean Baker's Anora blazes across the screen like a raucous fever dream, following a sex worker who marries a wealthy Russian heir in a whirlwind romance, only to face off against his family's attempts to break up the marriage.

The first hour plays like Pretty Woman if it had done a line of coke and decided to throw hands with capitalism. Mikey Madison's Annie bursts with the kind of anarchic energy that makes you want to burn down a country club while wearing last season's Gucci, delivering the kind of performance that makes you remember why you fell in love with movies in the first place. The film builds its fun with such deliberate care that when the gut-punch finally comes - and oh, does it come - you're left dealing with emotional damage that hits harder than your first therapy session.

I bring up Anora not just because it's excellent (though it is), but because it perfectly crystallises something that's been gnawing at me about contemporary cinema. We've somehow wandered into an era where "serious film" has become synonymous with "watching people suffer for two hours straight." Hollywood seems to have forgotten a fundamental truth about storytelling - that for a film to tackle something heavy, it doesn't need to be heavy-handed throughout. Billy Wilder diagnosed this problem decades ago when he said: "In certain pictures I do hope they will leave the cinema a little enriched, but I don't make them pay a buck and a half and then ram a lecture down their throats." His words feel almost prophetic now, as we've allowed prestige cinema to transform into a parade of trauma that mistakes relentless suffering for artistic merit.

The festival circuit and awards bodies have developed an almost algorithmic relationship with a particular brand of seriousness. Film critic Mattias Frey notes a troubling shift in recent decades: prestigious festivals, which effectively act as gatekeepers of critical taste, have fostered an environment where unrelenting gravity has become synonymous with depth. This isn't about individual films - many are masterfully crafted and deserve their accolades - but about a systemic bias within the critical establishment that continues to shape festival selections, awards consideration, and ultimately, industry standards. When every major festival lineup and awards season becomes a forecast of calculated solemnity, we've moved beyond curation into something more insidious: a feedback loop where filmmakers feel pressured to maintain a constant heaviness to be taken seriously, critics reward this choice as "brave" and "unflinching," and the cycle begins anew. This has created a critical ecosystem that has confused tonal monotony with complexity, as if a film's artistic merit can be measured by how thoroughly it drains its audience.

This isn't just critical posturing - audiences are actively rebelling against cinema's current love affair with misery. The evidence is everywhere online. Over on r/horror, viewers are done with every genre film doubling as a psychological excavation, yearning for the days when Evil Dead could thrill without forcing us to confront our deepest traumas.

One particularly insightful r/movies thread asks why modern films feel so "depressing, lonely and empty," noting how contemporary cinema has traded immersive worlds and fresh characters for isolated protagonists drowning in their own melancholy.

Even emerging filmmakers see the problem - there's this fascinating r/Filmmakers thread about how film students who sparkle with wit and creativity in their casual content suddenly transform into merchants of melancholy the moment they aim for "serious" filmmaking.

The science backs up what we're all feeling: researcher Roxane Cohen Silver has demonstrated that constant exposure to trauma-heavy narratives actually numbs viewers rather than deepening their engagement. VICE also captured this in their criticism of how this obsession with darkness, especially in Black cinema, has created a genuine hunger for stories that remember joy is also part of the human experience. We're witnessing a pushback against the peculiar notion that a film's significance must be measured by its capacity to devastate.

Frey puts an academic finger on our collective discomfort, arguing that we've created a critical environment where trauma has become a shortcut for significance. The math is devastatingly simple: these days, pain equals prestige. This reductive equation has created a self-perpetuating cycle between critics and filmmakers, narrowing cinema's emotional palette to various shades of misery. Take Life Itself or Dear Evan Hansen - films so desperate to be taken seriously that they mistake relentless darkness for depth, their important themes lost in a fog of calculated misery. The result is a cinema landscape where even the most vital stories risk losing their impact through sheer emotional monotony.

Here's where Baker's Anora becomes more than just a great film - it's a masterclass in emotional orchestration. The film's first half plays like a screwball comedy on steroids, with sharp dialogue that crackles between characters and absurdist situations that had critics at Vanity Fair praising its "raucous good time." Madison and Eydelshteyn's chemistry ignites the screen, their whirlwind romance and subsequent chaos unfolding with the kind of energetic abandon that makes you forget you're watching a film that's ultimately about very very very serious topics. This isn't just fun for fun's sake - it's strategic disarmament. Baker knows that by making us laugh, by letting us feel the pure joy of cinema, he's actually preparing us for a deeper emotional impact.

The same principle works brilliantly in Baby Reindeer (albeit it’s no “cinema”), where the darkly comic first half makes the series' eventual turn toward darkness feel like a punch to the solar plexus. Or Parasite, which spends its first half revelling in the dark comedy of its class warfare before sliding into tragedy with devastating precision. These works understand something fundamental about human emotion: contrast creates impact. When Get Out makes us laugh, it's not undermining its commentary on racism - it's making that commentary cut deeper. When Everything Everywhere All at Once fills us with joy and absurdity, it's not distracting from its exploration of generational trauma - it's making that trauma feel more real, more personal, more devastating.

This brings us to the broader cultural implications of our current trauma-obsessed cinema. We've somehow internalised the idea that constant heaviness equals importance, that unrelenting darkness equals depth. As Frank Capra once pointed out: “There are no rules in filmmaking. Only sins. And the cardinal sin is dullness”. By limiting our cinematic expression to a single emotional register, we're not just exhausting our audiences - we're potentially dulling our ability to process and engage with serious themes. When every film aims for the same emotional tenor, we risk creating a boy-who-cried-wolf scenario with trauma itself.

Let's be crystal clear here - this isn't about dismissing films that deal with trauma or suggesting that cinema should shy away from difficult subjects. When Schindler's List punches us in the gut, that heaviness serves a vital purpose. The issue isn't with individual films but with an industry-wide tilt toward emotional monotony, where films feel pressured to maintain a constant state of grievousness to be taken seriously. Somewhere along the way, Hollywood convinced itself that the only way to tell important stories was to drain them of joy, as if happiness and significance were somehow mutually exclusive. This mindset doesn't just limit our storytelling - it actually undermines our ability to process and understand trauma itself.

Anora handles its heavyweight themes differently. The film's exploration of even class warfare comes wrapped in moments of pure anarchic joy - a sex worker and a Russian heir falling in love in a Vegas chapel, bumbling goons failing spectacularly at their intimidation tactics, sharp-witted exchanges that would make Howard Hawks proud. We laugh, we fall in love with these characters, we get swept up in their chaos - and then, when the hammer falls, it falls with the weight of genuine emotional investment. Baker proves that fun isn't a distraction from serious themes. It's the spoonful of sugar that helps the medicine go down and actually stick in your system.

What's fascinating, as Parul Sehgal points out in The New Yorker article “The Case Against the Trauma Plot”, is how this compulsion has infected even our adaptations - recent versions of The Turn of the Screw now feel compelled to add sexual assault to the governess's backstory, while superhero narratives like WandaVision pile on trauma after trauma as if playing misery bingo. But there's hope in how some contemporary films are actively pushing back against this trend. For example, Taylor's They Cloned Tyrone brilliantly weaves sci-fi conspiracy with cultural trauma through the lens of pitch-black comedy, proving that even the heaviest themes about systemic racism can be tackled with wit and genre-bending imagination. Panahi's Hit The Road tackles exile and separation through moments of absurdist joy and playful family dynamics. These works remind us that characters can be complex without being reduced to their wounds, that they can surprise us, remain somewhat unknowable, and be more than just the sum of their traumas.

This resistance to trauma-only storytelling isn't new - some of cinema's most enduring classics have long understood the power of tonal complexity. Early Almodóvar films (a personal fave) like Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown dealt with serious themes while maintaining an almost manic sense of fun. Dr. Strangelove tackled nuclear annihilation through the lens of absurdist comedy. As Baker notes in his The Film Stage interview, "It’s important for me to inject humor in any story, even if it is a tragic story, or even if comedy itself might be inappropriate at the moment. As human beings, we find humor in sometimes-dark things."

The solution isn't to abandon serious subjects or to trivialize trauma - it's to remember that even the darkest stories exist within the full spectrum of human experience. The film industry's current obsession with constant heaviness isn't just boring - it's a fundamental misunderstanding of how we actually process life's biggest moments. Anora left me absolutely wrecked because Baker gets what so many prestige filmmakers have forgotten - that catching us off guard with joy makes the gut punch land harder.

Baker's final scene hammers this home better than any argument could: when cinema stops trying so hard to be "important" and just lets itself play across the full emotional keyboard, it leaves marks that last. I've spent years championing films that dare to make us feel more than one thing at a time, because I know in my bones that the best cinema doesn't just punch you in the gut - it takes you out dancing first. This isn't just my defence of fun at the movies - it's my manifesto for letting cinema be as gloriously messy as the lives it's trying to capture.

P.S. Apparently hitting that little heart button is the equivalent of leaving a good tip for the algorithm™ gods. So if you enjoyed this essay, please give it a like. And if you're sharing any of these takes in the wild (bless you), tag me - I love seeing which parts made you go "YES FINALLY SOMEONE SAID IT." Links are also deeply appreciated because, you know, sharing is caring and all that cinema-loving jazz.

Yes! The whole post is quotable; I entirely agree. I think Asian cinema is still telling good stories, but Hollywood seems out of touch. (Compare the Chinese TV adaptation of The Three-Body Problem with the Netflix version.) You mentioned "Everything, Everywhere,...". Another good example.

Modern western storytelling seems to me to have devolved to a narcissistic need for self-reflection. The need people have to "see themselves" in stories. Because modern culture is so traumatic (just scroll through Notes here), this leads to stories centered on our trauma.

Re characters drowning in their own trauma, private detective stories started doing that decades ago (to the point it was parodied). Lee Child's Jack Reacher stories feature a deliberate anti-anti-hero, a good old fashioned Lone Ranger type. We readers and viewers do indeed crave joy as well as sorrow. I'm reminded of the Lucinda Williams song. "I don't want you anymore 'cause you took my joy..."

Gonna see anora this weekend finally then I’ll come back to this!