this isn't debateslop

Hello my lovelies, I am back. And what we're dealing with is the exact opposite of the Aristotelian ideal.

I fled to my ancestral Greece two weeks ago, switched my phone to airplane mode, and vanished into a self-imposed exile from the internet. A digital detox on mountains first and a small seaside town second where spotty Wi-Fi and abundant Mythos beer conspired to keep me blissfully ignorant of the world’s churn. My family’s crumbling stone house perched (almost) above the Aegean became my refuge as I spent mornings swimming and afternoons making actual eye contact with people. Greece has always served as my reset button—a place where time works differently, where the news cycle feels irrelevant against the backdrop of ruins that have witnessed thousands of years of human folly. Then Charlie Kirk was assassinated, and even three thousand miles away, secluded in my Mediterranean cocoon, the news penetrated my sanctuary. My partner burst onto the terrace, phone in hand, shattering my offline idyll with headlines and notifications. Someone had shot the founder of Turning Point USA while he sat beneath a tent at his “Change My Mind” table—the theatrical debate format that had transformed him into a right-wing media sensation.

Upon returning to London, I found myself dropped into the strange spectacle of posthumous canonization. The man whose debate tactics I’d consistently found manipulative and intellectually dishonest was suddenly being transformed into a fallen champion of open discourse. “Charlie exemplified kindness, courage and a commitment to open debate, and he was a great debater, and we loved him for it.,” declared J.D Vance. “[Kirk] was a living embodiment of our First Amendment,” said Bari Weiss in her podcast. American Catholic prelate Cardinal Timothy Dolan went further still, describing Kirk as “He treated his opponents always with respect when they were verbally sparring…Because when your opponents sees this guy kind of respects me…I thought, ‘This guy can teach us something.”

These tributes came to my screen with such unanimous certainty that they almost made me question my own perception. Had I been watching different debates all these years? The Kirk I observed wasn’t engaging in good-faith exchanges aimed at uncovering truth. His format positioned a practiced debater against unprepared college students, filmed their exchanges, edited them down to moments where students appeared most flustered, then packaged them with titles like “Charlie Kirk DESTROYS Liberal Student’s Argument.” The power imbalance wasn’t incidental, of course. It was the entire point. When Kirk faced prepared opponents who challenged him substantively, he routinely pivoted to culture war talking points or employed rhetorical sleights of hand to avoid direct engagement. His debate style prioritized the appearance of winning over genuine exchange, creating content optimized for algorithmically-driven virality rather than intellectual discovery.

A week ago, Ryan Broderick’s Garbage Day newsletter (a long-time fave) featured an article examining the concept of “debateslop”. The piece cited Hussein Kesvani’s brilliant term —the perfect portmanteau to describe low-quality, antagonistic verbal sparring designed primarily for viral distribution rather than genuine intellectual exchange. Kesvani had originally applied the term to London’s Speaker’s Corner, a place I often pass during weekend walks through Hyde Park. Once a venue where figures like Marx, Lenin, and Orwell engaged in substantive discourse, Speaker’s Corner has devolved into a grotesque parody of public debate. Today, speakers arrive not to engage with the physical audience but to generate extremely online content for their extremely online followers. They bring camera crews, professional microphones, and honed provocations, seeking footage that will perform well on TikTok and YouTube. The parallels between what has happened to Speaker’s Corner and American college campuses struck me as uncanny—both spaces hollowed out and repurposed as content farms.

Look at us—descendants of the Agora where Socrates turned questions into art, heirs to a democratic tradition built on the premise that the clash of ideas yields gold, not wreckage. Now, someone can resurrect a Twitter beef from 2015 and drag it into 2025 with fresh screenshots and renewed outrage. The stakes are simultaneously meaningless (it’s just posting) and apocalyptic (your reputation lives forever in Google searches). Nobody learns to say “I was wrong about that” because the admission never expires. It just becomes ammunition for the next person who needs to prove their intellectual superiority.

Debateslop is where being wrong costs everything and being right changes nothing.

My own personal anger isn’t about Kirk, who simply mastered the rules of a game gone rotten. My fury is at how gladly we accepted these new terms without protest, barely noticing as substantive debate became as quaint and remote as dial-up modems. Films preserve a memory of something different, a hint that we once expected more from our public discourse than cheap dopamine hits wrapped in ideological wrapping paper. Who stole debate from us? And why did we hand over the keys so fucking willingly?

the debateslop formula

Arguably, the thieves weren’t masterminds in a smoke-filled room. They were opportunists who struck gold with a formula so potent it transformed public discourse into a circus of invented outrage. Let’s dissect the debateslop formula:

Prey selection: Kirk never debated equals—he targeted college students wandering past his booth between classes. I’ve watched dozens of these ambushes. An environmental science sophomore attempting to explain carbon sequestration while Kirk, twenty years her senior with a decade of media training, picks apart her language like a vulture. The power gap isn’t a bug; it’s the foundation. This creates dominance display—the audience doesn’t absorb content but witnesses hierarchical reinforcement, triggering primitive satisfaction at seeing social order affirmed.

Theatrical framing: The “Prove Me Wrong” table itself serves as psychological stagecraft. The person who approaches stands while Kirk sits. They entered his territory, played by his rules, used his microphone. Before a word is spoken, the spatial dynamics established who held authority. Media theorist Marshall McLuhan would recognize this right away—the medium constructs the message before any content exists. The physical arrangement communicates: “This is a performance with predetermined roles.”

Tactical arsenal: While opponents attempt good-faith exchange, Kirk deployed techniques no amateur could counter: the Gish gallop (drowning opponents in too many points to address), false equivalence, strategic interruption, and topic-pivoting when cornered. These do not encourage debate. They’re conversation terminators since the cognitive load becomes overwhelming by design. Neuroscience shows our working memory can juggle 4-7 items simultaneously—when someone hurls 15 points in 30 seconds, mental overload guarantees stumbling.

Extraction economy: What really happened undergoes alchemical post-production transformation. A ten-minute exchange ends up being a forty-second clip where only Kirk appeared coherent. His opponents’ strongest arguments vanished; their weakest moments defined them forever. The TikTok account that recirculates these segments grabbed seven million followers in eighteen months, turning human dignity into extractable resource.

Tribal validation: Eli Finkel, professor and co-director of Northwestern University’s Litowitz Center for Enlightened Disagreement, discovered viewers tune in not for education but vindication. “They want to watch their champion defeat, and ideally embarrass, ‘those idiots’ on the other side.” This taps something older than politics: coalitional psychology. Our brain’s hardwired reward for witnessing our tribe dominate rivals. The dopamine hit doesn’t come from learning, but from winning.

This five-part formula of debateslop, ultimately, creates a “market for lemons” situation in the attention economy. When consumers can’t easily distinguish quality (substantive debate) from garbage (performative destruction) before investing attention, low-quality content drives out high-quality alternatives. Yesterday I watched a compilation of “debate wins” from across the political spectrum, the tactics identical regardless of ideology. Four hours later my brain felt like it had been dipped in battery acid. Not because the topics were controversial—I live for that shit—but because nobody was actually debating. They were performing combat for an audience, manufacturing conflict for clicks, turning discourse into WWE with footnotes.

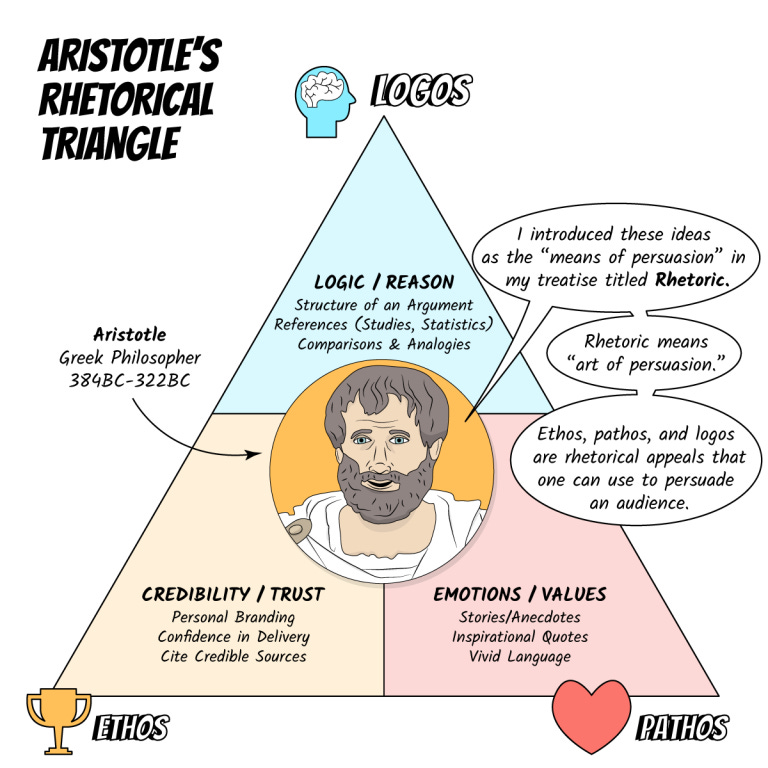

I grabbed a bottle of wine and pulled up Aristotle’s Rhetoric on my Kindle. Dramatic? Yes. Necessary? Absolutely. The old Greek had rules for this stuff, and nobody follows them anymore. Debate requires three elements in balance:

logos (argument backed by evidence)

ethos (speaker credibility)

and pathos (appropriate emotional appeal)

(Manipulate one at the expense of the others and the whole enterprise falls apart.)

The Socratic dialogues show debate as midwifery—bringing forth ideas through skilled questioning. Medieval disputations required opponents to summarize each other’s positions to their satisfaction before responding. The Talmud preserves minority viewpoints alongside majority decisions. Ancient debate traditions would show you that the goal isn’t victory but collective advancement toward truth.

Daniel Dennett calls this the “charitable interpretation principle”, steel-manning rather than straw-manning your opponent’s position. Philosopher John Stuart Mill insisted we must understand opposing arguments in their strongest form, not to be polite but because it’s epistemologically necessary. You don’t even understand your own position until you truly grasp its counterarguments.

This standard exists in cinema.

Which is why on my part, what I’ve been doing these past few days is mainlining fictional debates from great films—a bizarre form of self-medication that’s yielding unexpected insights. My scene selection spans courtroom confrontations to philosophical standoffs to political showdowns, each containing a forgotten language of productive disagreement. Unlike debateslop, these fictional exchanges remind us that the most electrifying debates aren’t demolitions but unprecedented discoveries.

Let me show you.

“Before Sunrise” (1995)

when debate becomes flirtation

I watched Before Sunrise the first time in a shitty flatshare apartment with a guy I was trying to get it on with. We were both pretending to be more intellectual than we were, so naturally we picked a Linklater film. The apartment smelled like weed and frozen pizza, and I remember thinking, “God, I wish someone would talk to me like Jesse talks to Céline.” Not my date, obviously. He kept pausing the movie to tell me he “got” exactly what Linklater was doing with the mise-en-scène. Sir, you’re an accounting major.

But back to debates! Remember that scene on the train where these two beautiful strangers debate reincarnation? It’s barely five minutes into the movie, and Jesse (peak 90s Ethan Hawke, all floppy hair and performative cynicism) starts pontificating about his theory that we’re all reincarnated versions of ourselves — like we live the same life over and over, just without knowing it. Céline (Julie Delpy, the French dream girl Americans didn’t realize they needed) listens with this mix of amusement and genuine interest. She doesn’t immediately agree or disagree, but you can see her mentally trying his idea on like it’s a vintage jacket at a thrift store. She’s figuring out if it fits her worldview, but also if he fits her worldview.

What makes this debate so wonderful is that it’s not really about reincarnation at all. It’s about two people figuring out if they’re intellectually compatible. The debate is foreplay. The philosophical topic is just a pretense to feel each other out (mentally, I mean, though the physical happens later). Jesse isn’t trying to win; he’s trying to impress. Céline isn’t trying to counter; she’s trying to connect. Their body language shows it too — they start physically mirroring each other, leaning in at the same moments. When she challenges him on his theory, there’s no defensiveness in his response. Instead, there’s a little smile, like: “Good, you’re playing too.” The disagreement is what builds attraction. This is why we all wanted to be in the debate club but ended up just arguing with our roommates about who ate the last yogurt.

Linguists talk about this thing called “high-involvement conversational style” where interruptions and overlapping speech aren’t rude. They show engagement! That’s what’s happening here. In many movie debates, characters wait their turn to deliver perfectly crafted zingers. But Jesse and Céline step on each other’s sentences, laugh through their points, and gesture wildly when words fail. It’s messy like real conversation. It’s messy like real attraction. And that’s what makes it one of cinema’s greatest debates — it shows how intellectual sparring is sometimes just another way of saying “I find you fascinating, and I want you to find me fascinating too.” I’ve seen friends this approach at bars with mixed results, often ending with them alone, explaining Kierkegaard to a half-empty beer glass. But for Jesse and Céline, it works. Some people get all the luck.

“The Great Debaters” (2007)

when David meets Goliath

Harvard’s opulent debate hall, 1935. Three Black students from Wiley College walk into the whitest room in America. The audience stares. The air crackles with tension thicker than my aunt’s holiday gravy. Denzel Washington directed this scene knowing exactly what he was doing: crafting a moment where intellect becomes a weapon against institutional racism.

James Farmer Jr. (played by Denzel Whitaker) stands at the podium, initially rattled. His hands shake. He sweats. Then something clicks. The transformation unfolds as he reframes civil disobedience from an abstract concept to a visceral necessity. “In the face of injustice, I would say that civil disobedience is not just a right, but an obligation.” Farmer pivots from theoretical arguments to lived experience, switching between formal rhetoric and raw testimony, a technique that you may now know as code-switching. My high school debate coach tried teaching us this. He failed spectacularly, mostly because he was a 50-year-old white dude whose idea of “keeping it real” was wearing Converse with his suits.

Farmer’s rhetoric teaches us that elite debate spaces demand you speak their language while simultaneously subverting it. He quotes St. Augustine and Gandhi in the same breath as referencing the brutality of Jim Crow—essentially saying “I’ll play your game, but I’ll change the rules.” When Harvard’s team tries trapping him in logical fallacies about law versus justice, Farmer sidesteps by recounting a lynching he witnessed as a child. The room freezes. He’s broken the fourth wall of debate—mentioning the unmentionable.

The technical brilliance comes in Farmer’s tempo manipulation, speeding through statistics then slowing dramatically for emotional appeals, an approach presidential speechwriters still steal today (Obama’s 2008 speeches? Textbook Farmer flow). Meanwhile, his teammate Samantha (Jurnee Smollett-Bell) quietly nods, giving him unspoken permission to go off-script.

The Harvard scene reveals debate’s highest form: not winning arguments but transforming hearts. When Farmer concludes with “That’s my judge,” turning toward the all-white audience instead of the official judge, he acknowledges the true battleground: public consciousness. Every great debate since, from Baldwin vs. Buckley to the Zuckerberg congressional hearings (though those were less debate and more watching a lizard person attempt human expressions), follows this pattern of appealing beyond the immediate authority to a higher court of human dignity.

Washington shot this scene with minimal cuts during Farmer’s final argument, letting the monologue breathe in real time, which is in exact opposition with today’s TikTok-addled video editing. The cinematography lesson here? Sometimes you just need to shut up and let genius speak for itself.

“Frost/Nixon” (2008)

when rhetorical pugilism is on full display

Ron Howard, a director whose oeuvre often skews toward the saccharine, somehow crafted a duel of minds so taut in “Frost/Nixon” it makes the average Aaron Sorkin walk-and-talk seem like preschoolers arguing over sandbox territory. Frank Langella’s Nixon and Michael Sheen’s Frost circle each other like Socratic gladiators, demonstrating that the most cataclysmic weapons aren’t nuclear but linguistic.

Nixon deploys prolixity as obfuscation, drowning his interlocutor in verbal quicksand. Every debate champion knows this tactic: speak at such length that your opponent forgets the original question, the audience loses consciousness, and time itself begins to warp. It’s the same technique my ex used when I asked why there were mysterious late night charges to Uber Eats on our shared debit card. Nixon’s seemingly meandering monologues reveal Foucault’s theory of power-knowledge in action—controlling discourse equals controlling reality. His filibustering transforms the interview from interrogation into autobiography, a prime case in narrative hijacking that contemporary politicians have turned into their bread and butter (see: every presidential debate since 2016, where answering the actual question posed became as optional as reading the Instagram terms of service).

Frost’s genius emerges in his strategic deployment of silence—something Japanese negotiators call ma, the powerful empty space between words. While American debate tradition rewards verbal diarrhea, Frost recognizes that saying nothing often forces others to fill the void, usually with damning admissions. The camera lingers on these moments, creating excruciating temporal expansion. Howard uses cinematic grammar of debate that requires these uncomfortable lacunae—the visual equivalent of Harold Pinter’s famous pauses, where the unsaid carries more weight than explicit declaration. I tried this technique once during a salary negotiation and ended up with a borderline salary cut but…still, theory versus execution.

Psychologically, Frost employs what negotiation theorist William Ury names “going to the balcony”—maintaining metacognitive awareness while engaged in conflict. When Nixon attempts dominance displays (leaning forward, invading personal space, weaponizing familiarity with that midnight phone call), Frost absorbs these blows without counterattacking immediately. He stockpiles ammunition for the perfect moment. The debate ends up being the Aristotelian rhetoric incarnate that we mentioned earlier: ethos (credibility) being established, pathos (emotion) being manipulated, and logos (logic) delivering the coup de grâce.

The denouement, Nixon’s confession that “when the president does it, that means it is not illegal”, represents the apotheosis of the “unthought known,” when a person finally articulates what they’ve always unconsciously believed. Langella delivers this with the gravitas of a Greek tragic hero experiencing anagnorisis: that pernicious moment of recognition that transforms character and audience alike.

So next time you’re locked in argument with someone who thinks pineapple belongs on pizza or that cinema is “dead,” remember Frost’s arsenal: strategic silence, accumulated evidence deployed at exactly the right moment, and the power of simply letting someone talk themselves into a corner. The healthiest debates aren’t about domination but illumination—creating conditions where truth can emerge, even from the most reluctant sources. Sometimes that requires 28 hours of interview footage and a production budget in the millions. But the principles remain accessible even to those of us whose debates occur over lukewarm Nespresso coffee rather than under hot studio lights.

“12 Angry Men” (1957)

when debate transcends the noise of certainty

Of all the scenes we’ve dug through, I gotta say the debate in the 1957 version of “12 Angry Men” stands as a particularly intriguing outlier. Not because you’ve all seen it, but because amid a film about reasonable doubt and judicial fairness, Lumet sneaks in this philosophical sidebar between Fonda and Cobb that manages to reflect the film’s central tensions while feeling completely removed from them.

The 1957 film traps twelve men in a sweltering jury room as they decide whether to send a young man to the electric chair. Eleven jurors vote guilty immediately. Only Henry Fonda’s Juror #8 holds out, and what follows is essentially the perfect textbook on how to change minds under pressure.

About thirty minutes in, the film delivers one of its most methodical debates when the jurors examine whether an elderly witness could have heard the defendant yell “I’m going to kill you” before the murder. The old man testified he heard these words through his apartment door, over the noise of a passing elevated train.

The scene unfolds as follows: Lee J. Cobb’s Juror #3 insists the old man’s testimony is rock solid. Fonda asks how the witness could hear anything with an elevated train roaring past his window. Cobb dismisses this doubt with the certainty of someone who’s never questioned his own assumptions. E.G. Marshall’s Juror #4, the coldly logical stockbroker, backs him up, claiming the train wouldn’t have drowned out the boy’s voice.

Fonda doesn’t get combative. Instead, he asks questions: “How long does it take a six-car el train to pass a given point?” This approach – questioning premises rather than conclusions – completely reframes the debate. The jurors realize nobody knows exactly how long the train would take to pass. Nobody knows exactly how loud it would be. What seemed like certainty begins to crumble under the weight of simple, factual questions.

What’s happening philosophically is a classic Socratic dismantling – Fonda isn’t telling anyone they’re wrong; he’s asking questions that lead them to recognize the limitations of their own knowledge. The epistemological shift is palpable. Several jurors who were absolutely certain of guilt begin shifting to a place of doubt, not because Fonda has better arguments, but because he exposes how much they don’t know.

The scene works as an astonishing example of a healthy debate because both sides actually listen. Fonda doesn’t interrupt or dismiss Cobb’s perspective. He absorbs it, considers it, then tests it against reality. Cobb, despite his anger, engages with the substance of Fonda’s doubts rather than attacking his character. There’s a mutual respect underpinning their disagreement – they both want truth, they just have different ideas about what constitutes it.

From a psychological perspective, what we’re watching is cognitive dissonance in real time. Cobb physically recoils when his certainty is challenged. His body language stiffens. His voice gets louder. These are classic defense mechanisms when core beliefs are threatened. The other jurors exhibit varying forms of this discomfort – some retreat into silence, others become aggressive. The film captures how emotionally difficult it is to change your mind, especially when others are watching (which is what the entire world does online these days).

I’ve sat through enough family dinners to know that most real-life arguments don’t work this way. We talk over each other. We resort to personal attacks. We refuse to acknowledge valid points. What makes this scene so valuable is how it demonstrates that productive disagreement requires both intellectual rigor and emotional restraint. Fonda never makes Cobb feel stupid for being wrong. He creates space for him to revise his position without losing face.

debating the undebateable

Three years ago, a friend told me something during a dinner that completely changed how I think about immigration policy. I can’t even remember exactly what he said, just that it was specific, personal, and hadn’t occurred to me before. The conversation lasted maybe ten minutes. I walked away from that dinner with a slightly different perspective on something I’d been certain about. It felt like the most natural thing in the world. Now that same same sends me links to videos of pundits “destroying” people who disagree with him, and I can’t figure out how to tell him that the thing he’s celebrating is the exact opposite of the thing that changed my mind that night. The intimacy required for genuine persuasion has been replaced by the performance of persuasion. I’m not even sure he remembers that dinner conversation, but I think about it constantly.

At this stage, I do wonder if I’m mourning something that never really existed, at least not in the pure form I imagine. There’s a chance I’m romanticizing film debates because they’re fictional—written by people who had time to craft the perfect comeback and choreograph the ideal response. Real debate has always been messy, imperfect, riddled with ego and ulterior motives. But even accounting for nostalgia, I used to have friends who could argue with me for hours without either of us feeling like our fundamental humanity was under attack. We could disagree about politics, art, philosophy, and still share a meal afterward. Now every conversation feels weaponized, every opinion a potential cause for exile.

I miss being wrong about things without it becoming a public referendum on my character. I miss the possibility of having my mind changed by someone I disagreed with. I miss arguing about ideas rather than arguing about each other. Most of all, I miss the assumption of good faith—the belief that the person across from me was trying to understand something true rather than trying to destroy me for points (and trust me, as an online writer of several years, I’ve had and still have plenty of people that continue to do just that). That assumption might have been naive, but it was also the foundation of everything worthwhile about intellectual life. Without it, we’re all just waiting for our turn to be right.

So what can be done?

Delete your drafts folder. All of it. Those angry responses you wrote but never sent, those perfectly crafted comebacks you’ve been saving for the right moment, those receipts you screenshotted in case you need them later—delete. Stop stockpiling ammunition for arguments you haven’t had yet. Stop preparing for intellectual warfare. The habit of collecting evidence against people you disagree with has turned your brain into a prosecutor’s office where everyone is presumed guilty until proven innocent. Try going into conversations without backup plans or exit strategies. Leave your phone in another room during dinner party discussions. Join book clubs that meet in physical spaces where WiFi is not quite working. Attend lectures where questions have to be asked out loud, in real time, without live reactions or comment threads. Go to film festivals and stick for the conversation at the bar after. Find environments where you can’t quickly Google counterarguments or fact-check your opponent’s claims mid-conversation. Load up Aristotle on Kindle.

Practice thinking on your feet instead of thinking with your fingertips.

A final note for people with taste 🫦

While the internet’s prioritizing hot takes and SEO-optimized nothingness, I’m here building a sanctuary for people who believe film and television criticism can be thoughtful, accessible and fun all at once.

For the price of a truly mediocre sandwich, consider joining the resistance with a paid subscription – it keeps independent film writing alive and the algorithms at bay.

Plus, you’ll get exclusive access to After Credits, my monthly handpicked selection of films & tv shows that will stop you from doomscrolling Netflix AND access to my more personal posts.

Now go forth and raise those standards, darling.

- Sophie x

As always, your observations are so sharp. Oh to be blissfully unplugged in Greece for even a day would be a dream for an American such as I.

Welcome back!

I was blissfully unaware of Kirk before the events last week and I didn't realize his whole thing was being a 30 yo man debating children? (no offense to college students but like he wasn't even debating his peers?)