i let paul thomas anderson diagnose america so you don't have to

PTA's America is sick, hot, and probably contagious.

I never thought I’d be crying over citizenship paperwork at a random Tuesday evening, but here we are. My British passport application sits open on my laptop—all the boxes checked, all the documents marked, ten years of my life reduced to form fields and reference numbers. The application fee alone costs more than my first month’s rent when I moved to London. But I pay it because I have no choice. After a decade building a life here, friends, career, favorite pubs, secret walking routes through Hackney Marshes, Farage’s Reform UK threatens to dissolve settled status protections with each xenophobic speech. The same man who rode a Brexit bus plastered with immigration lies now polls at 19% while promising to “send them all back.”

The cinema offered escape last week, two hours of darkness where my immigration status didn’t matter. Instead, I found myself watching Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another and seeing my own anxieties reflected on screen in ways I didn’t expect.

The film drops us immediately into the middle of DiCaprio’s former revolutionary Bob Ferguson living off-grid with his teenage daughter, paranoid and haunted by his past. The premise alone tells you everything about Anderson’s ambitions with this one. DiCaprio plays Bob Ferguson, once known as “Ghetto Pat,” a former radical who must rescue his daughter from the clutches of a military official (Sean Penn’s Colonel Lockjaw) while confronting the consequences of his past militancy. Anderson has taken Pynchon’s “Vineland”—a novel about 60s revolutionaries facing Reagan’s America—and transformed it into a story about what happens when yesterday’s radical idealism crashes into today’s authoritarian reality. Unfortunately, this is also America in 2025, where Charlie Kirk’s assassination two weeks ago was followed by Trump’s declaration of Antifa as a domestic terrorist organization, where ICE detention centers are being attacked, where edgelord political violence has become our new background noise.

This is why I’ve come to believe Paul Thomas Anderson might be one of America’s greatest diagnosticians. I realize that’s a bold claim but I’ve always found this guy’s got some sort of sixth sense for American neuroses—catching its cultural illnesses before we even feel the symptoms. Because his work doesn’t document America. It anticipates it. You know how dogs can smell cancer? Anderson can smell fascism brewing in oil fields, cults forming in post-war spiritual vacuums, incel rage bubbling under Frank TJ Mackey’s pickup artist bullshit. His camera cuts through America’s self-mythology with supreme clairvoyance. Critics may call it “American decline,” but that neglects what Anderson truly captures: the raw nerve endings of a culture perpetually at war with itself.

And if I’m right about this, his work is beyond brilliant cinema. It’s essential viewing for anyone trying to understand how the hell America got here.

Sophie’s note: This essay includes spoilers of PTA films so please tread carefully ❤️

I. the last 90s: documenting cultural rot at ground zero

I wasn’t in America when Hard Eight premiered at Sundance in 1996, but my family vicariously lived through the global worship of American capitalism in the 90s. My relatives spoke about Clinton’s economy the way people discuss miracle cures. The Dow Jones kept climbing. Unemployment kept falling. Silicon Valley was minting millionaires. Francis Fukuyama had published “The End of History” a few years prior declaring liberal democracy’s ultimate triumph. America had won! Everyone could get rich! You just had to learn the system!

Paul Thomas Anderson’s debut opens on Philip Baker Hall in an immaculate suit, sitting across from John C. Reilly, who’s broke and filthy outside a Nevada diner. Hall’s Sydney, a professional gambler with impeccable manners, offers to teach Reilly’s John how to game casino comp systems: the right tips, the correct posture, how to perform solvency when you’re drowning. Roger Ebert called the characters original and compelling which is accurate but Anderson’s better achievement sits in how meticulously he mapped the collapse of every American institution that used to mean something. Family? John’s mother just died and he can’t afford her funeral. Church? Nobody mentions God. Honest work? The film unfolds entirely in casinos, diners, and cheap motels where people manufacture luck for a living. The only honor code remaining operates among gamblers and criminals—people who at least admit the game is rigged.

Sydney mentors John out of guilt, not love. He murdered John’s father years earlier. The surrogate father-son bond everyone celebrates in this film is a transaction. Redemption requires collateral. Morality has terms and conditions. Even the warm communal bonds Anderson would become famous for, the “found families” critics adore in his work, only cohere around shared cons. Sydney doesn’t adopt John because he needs a son. He’s repaying a blood debt with room service and blackjack lessons. The film ends with Sydney executing a man in a motel bathtub to protect his investment in John’s future. That’s not what family does. That’s what capitalism looks like with a human face.

Boogie Nights exploded into theaters October 1997, the same month the Dow broke 8,000 for the first time. America was flying. Robert Rubin’s Treasury Department had convinced everyone that deregulation plus globalization equaled permanent prosperity. NAFTA was funneling cheap goods north. Telecommunications Act was setting up the coming internet gold rush. Greenspan kept interest rates low. Money flowed. Anderson was busy making a film that best showed how American capitalism swallows intimacy whole, then spits out the commodified version.

Eddie Adams becomes Dirk Diggler in 1977—the year after America’s bicentennial, right when the post-Watergate angst was curdling into something worse. Burt Reynolds’s Jack Horner genuinely believes he can shoot “artistic” pornography, films audiences would watch even after orgasm. Julianne Moore’s Amber Waves offers maternal love to teenage runaways. Mark Wahlberg’s Dirk treats his body like Intel treated microchips: a product to manufacture at scale, a gift to monetize, a resource to optimize. They’re building something! A family! A legacy! Capitalism promises you can have both intimacy and profit, connection and scale, authenticity and distribution. Anderson films the lie in wide, languid Steadicam shots that make the San Fernando Valley look like Camelot bathed in golden-hour light.

Then the ‘80s arrive and video replaces film. Art becomes content. Jack’s films degrade into gynecological loops shot in a day. The family fractures. Cocaine replaces community. Dirk can’t achieve erection anymore because performing intimacy for money eventually murders your capacity to feel anything that isn’t transactional. Everyone got exactly what they wanted—fame, money, houses, cars—and somehow ended up bankrupt anyway. The American Dream didn’t fail these characters. It succeeded as engineered, then sent the bill. Anderson released this film the same year Titanic became the highest-grossing movie ever made.

By December 1999, Anderson had stopped bothering with subtlety. Magnolia opens with a narrator explaining impossible coincidences, then rains literal biblical frogs on the San Fernando Valley. Tom Cruise plays Frank T.J. Mackey, a self-help guru running “Seduce and Destroy” seminars where he teaches hotel ballrooms full of men to “respect the cock” and “tame the cunt.” Ross Jeffries—the real pickup artist who inspired Mackey—was actually holding these seminars in the late ‘90s, teaching neuro-linguistic programming techniques disguised as seduction advice to men who believed women were obstacles between them and sex. In other words, Anderson was documenting incel culture’s formation in real time while everyone else was celebrating dot-com IPOs and Clinton’s 4% unemployment rate.

Frank’s entire philosophy treats women as territory to conquer, intimacy as weakness to exploit, masculinity as theater requiring constant vigilance. He may tell you he’s teaching connection, but he’s actually teaching warfare. And it works. The men in those hotel ballrooms are ecstatic. They finally have a system, a framework, a way to win. April Grace’s journalist Gwenovier interviews Frank and methodically dismantles his mythology: the invented education credentials, the fabricated family history, the abandoned dying mother he’s airbrushed from his biography. Cruise’s face performs something extraordinary during this scene—the carefully constructed bravado collapses and suddenly we’re watching a terrified kid who built an empire on rage because vulnerability would require admitting his father abandoned him when he was fourteen.

Anderson released Magnolia weeks before Y2K, during peak American confidence. Technology was ascending. The future looked inevitable. In the end, John C. Reilly’s cop might get the girl. Melora Walters’s traumatized daughter might find peace. Tom Cruise’s Frank might reconcile with his dying father before the morphine kicks in. It’s the most optimistic ending Anderson could have filmed, yet it still required frogs falling from the sky, plagues manifesting, God physically intervening to shatter everyone’s constructed lies before healing becomes even remotely possible. The film is screaming:

These institutions are rotten.

These families are corroded.

This masculinity is poisonous.

This is not sustainable.

The director released three films between 1996 and 1999 that all conclude the same message: damaged people theoretically capable of redemption if they survive what’s coming. Sydney sits alone after executing someone. Dirk masturbates in front of strangers for money. Frank weeps at his father’s deathbed. Each film offers the faintest possibility of change—maybe Sydney finds peace, maybe Dirk gets clean, maybe Frank learns to feel—but Anderson knows better. He knows these characters are trapped in systems designed to extract everything valuable from them before discarding the husk. The casinos will keep operating. The porn industry will keep filming. The grifters will keep “teaching”. The machinery doesn’t care if you find redemption. It just needs fresh bodies.

II. the late 00s: excavating american foundations

Northern Rock collapsed September 2007, and there were film critics watching There Will Be Blood premiere at the film festivals while American banks queued for government handouts like junkies at a methadone clinic. Daniel Plainview onscreen, alone in a hole, hacking at rocks until his leg snaps—and I remember thinking, this is every hedge fund manager right now, leveraging themselves into dust for one more quarter of profit. The film opens without dialogue for fifteen minutes. Just breathing and breaking. A man dragging his shattered body across desert to file a claim. Goldman Sachs sold mortgage packages to pension funds while betting against them—that’s Plainview’s business model, drilling sideways into Eli’s land, taking what’s underneath while maintaining perfect deniability. “I drink your milkshake” became a meme because it explained 2008 better than most economists at the time.

Your mortgage is my milkshake.

Your pension is my milkshake.

Your future is my milkshake, and I’ve already drunk it.

Jonny Greenwood’s score turned oil drilling into demonic possession. Those strings scraping against each other, the percussion that sounds like industrial machinery achieving consciousness. H.W. loses his hearing because American progress demands sensory sacrifice. We deafen ourselves to function. The explosion that makes Plainview rich destroys his capacity for human connection. Oil gushers require child sacrifice. Fortunes demand funerals.

Paul Dano plays Eli Sunday as prosperity gospel before prosperity gospel had a name. He channels the Holy Spirit through his congregation the way Plainview channels oil through his derricks. Both men understand performance as currency. Eli’s church services—writhing on the floor, speaking in tongues, casting out demons—mirror Alan Greenspan testifying before Congress, swearing the free market would self-regulate. The scene where Plainview forces Eli to denounce himself—”I am a false prophet, God is a superstition”—while slapping him bloody happened to every JP Morgan exec in 2008, except they kept their jobs.

Then came 2012. Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes split over Scientology in June, and by September The Master was in theaters. But really, look at what else was happening: CrossFit had just gone national, turning strip malls into pain cults where people paid $200 a month to destroy their bodies together. Bikram Choudhury was collecting Rolls-Royces and rape allegations while teaching executives to sweat toxins that didn’t exist. Keith Raniere was branding women in Albany basements between executive success seminars. NXIVM, Bikram, CrossFit—Americans were joining cults faster than Netflix could document them.

The Secret still topped bestseller lists in 2012. Oprah was pushing Eckhart Tolle to housewives who needed their suffering to have cosmic significance. Everyone manifesting abundance while actual abundance was being redistributed upward at record speed. “You create your own reality,” every guru promised, which is exactly what Dodd tells Freddie: “You are not your body, you are not your emotions, you are a spirit of infinite capability.”

Into this spiritual wasteland, Anderson drops Freddie Quell, drinking paint thinner mixed with torpedo fuel because that’s his morning routine. Phoenix plays him like America’s id went to war and came back speaking only in violence and cum. First scene after the war: he’s finger-fucking a woman made of sand. This is victory? This is what America fought for? To come home so scrambled we’re humping dirt and drinking photo-developing fluid?

Lancaster Dodd finds him passed out on his yacht because of course he does, gurus can smell damage like sharks smell blood. Philip Seymour Hoffman sweats through every frame, and watch his eyes during those processing sessions—that millisecond of panic before he invents another trillion-year-old trauma, another past life, another explanation for why Freddie’s so fucked up that has nothing to do with dropping atomic bombs on civilians. “You’ve lived for billions of years,” Dodd tells him, which is exactly what L. Ron Hubbard told traumatized veterans in 1950. Americans bought it then because admitting the war broke them was impossible. The West bought it in 2012 because admitting capitalism broke us was impossible. The West is buying it right now in whatever form it’s currently taking: manifestation, microdosing, cold plunges, whatever helps you not think about what you did to survive.

Amy Adams plays Peggy Dodd like a knife pretending to be a spoon. She’s the true believer, the enforcer, jerking Dodd off in the bathroom while lecturing him about his drinking—the perfect American combination of sexual repression and spiritual authority. She knows he’s making it up. She tells Freddie point blank: “This is something he’s creating.” But she also knows the creation is working, the money’s flowing, the followers are following. In 2012, megachurch pastors were getting caught with rent boys weekly. Yoga teachers were “adjusting” students into sexual assault and calling it tantra. Wellness had become another word for “how much violation can we rebrand as healing?”.

The 65mm film stock makes every pore visible. That first processing session between Freddie and Dodd, just eyes and sweat and barely controlled violence, could be any post-2008 therapy modality Americans were throwing money at. EMDR in strip mall offices. Ayahuasca ceremonies in Bushwick warehouses. Ketamine clinics next to juice bars. Anything, anything, anything except admitting the system itself is the trauma.

Plainview creates the wound, Dodd sells the bandage. One extracts value, one processes trauma. One builds the machine that breaks you, the other charges admission to explain why you’re broken. The revelation isn’t that they’re con artists—it’s that Plainview and Dodd win. They get the mansions, the followers, the satisfaction of dying rich while everyone else dies trying. Eli gets his skull caved in. Freddie ends up on an English beach, still broken, whispering processing questions to sand that will never answer.

The distance between 2007’s financial collapse and 2012’s spiritual aftermath taught America that revolution was impossible, but personal transformation? That you could buy. That you could join. That you could practice every morning at 6 AM for $200 a month. So when faced with systemic collapse or CrossFit, we chose CrossFit. When offered revolution or regression therapy, we chose regression. When given the option between admitting capitalism had conned us or joining a smaller, more manageable cult, we chose the cult. Every time.

According to Anderson, America chose the smaller con because the smaller con makes it feel special instead of stupid. The smaller con has a charismatic leader who knows our name. The smaller con promises transformation in 90 days or your money back. Scientology over socialism. Self-help over social change. Personal brands over people’s revolution. These two films work as a pair: origin and symptom, cause and effect, the first con and every con that follows.

II. the break: it’s all starting to look different

Michael Brown died in Ferguson, August 2014. Six bullets, eighteen years old, body in the street for four hours while America decided whether to care. I was in Athens studying at the time, and the livestreams looked familiar—tear gas, riot shields, teenagers throwing stones at tanks. Greece had been doing this dance since 2008, since our own cops killed our own kids. But America still thought it was special, still thought its violence was exceptional rather than standard operating procedure. Inherent Vice hit theaters that October like a transmission from 1970 warning us about right now.

The plot makes no sense on purpose: Mickey Wolfmann vanishes, the Golden Fang might be heroin or dentistry or both, everyone’s a cop or pretending to be. That’s the point. Conspiracy doesn’t need logic when it has capital. Doc Sportello keeps investigating crimes that have already been legalized, following leads that circle back to the same conclusion. The hippies lost before they started. Flower power was always about property values. Josh Brolin’s Bigfoot—fascist cop who eats frozen bananas like they’re cocks—isn’t Doc’s opposite. They’re coworkers who don’t know it yet. By film’s end they’re literally working together, sharing intelligence, because resistance and repression always discover they’re different departments of the same company.

Robert Elswit’s camera makes 1970 L.A. look like California feels: beautiful and brain-damaged, sun-bleached and rotten, paradise with melanoma. Colors bleed wrong. Focus drifts. Everything’s too bright or suddenly dark because that’s neoliberalism. You never know if you’re hallucinating or if reality actually looks like this now. Anderson filmed what Pynchon wrote: the counterculture was a business opportunity from day one. Tune in, turn on, drop out—then pay rent, get dental insurance, die in debt like everyone else. Doc investigates but there’s nothing to investigate. The case was closed before it opened. The hippies were always going to become their parents. The protesters were always going to become cops.

The system won in 1970. The system won in 2014. The system wins by letting you think you’re resisting while you’re actually participating. Occupy thought it was threatening Wall Street. Wall Street thought Occupy was cute. America had already ordered more tear gas. Anderson made a film about how the 1960s died, but really, he documented how American resistance always dies—not through suppression but absorption, not through defeat but employment. The revolution doesn’t get televised. It gets syndicated.

From there, PTA pivoted indoors. After charting the macro-decay, he narrowed into the micro: domestic economies of power, interpersonal capitalism, intimacy as transaction. Phantom Thread and Licorice Pizza look, on the surface, like reprieves. However, they’re just updates to the same operating system.

I remember watching Phantom Thread in 2017 and thinking: this feels less like a romance than a hostage negotiation. Reynolds is this fussy, brittle man who treats love like an engineering problem. Alma figures out pretty quickly that the only way to stay close to him is to wreck his machinery. So she poisons him. Not once. Repeatedly. And the twist is that he welcomes it. Reynolds loves Alma because she interrupts his operations. Alma loves Reynolds because he gives her proximity to power. Their bond is forged through sabotage, bargaining, and control (which is exactly what relationships in the late 2010s felt like after the explosion of “emotional labor” discourse). Suddenly intimacy was (and continues to be) a battlefield of economics: who cooks, who cleans, who makes the money, who has to shrink themselves so the other one can shine. It sounds grotesque because it is but grotesque in the exact way love felt when every article was telling you your partner was secretly your boss.

By the time Licorice Pizza showed up, the tone had shifted. This one pretended to be lighter, messier, sweeter — but the rot is still there. Gary is basically a walking sales pitch and the internet was right there with him. This was the peak of TikTok hustle culture, dropshipping teens and YouTubers running shell companies. Anderson stages it in the valley of the 1970s, but the rhythm is pure 2010s Los Angeles: kids trying to become empires before they’re even old enough to rent a car. Every conversation is another scheme, the waterbeds, the pinball hustle, the political campaigns. And Alana keeps orbiting him, half disgusted, half addicted to the chaos.

That chaos made perfect sense in 2021. The whole world had just spent a year online, trapped in an economy where every interaction looked like a pitch deck. Dating apps, brand collabs, Clubhouse — intimacy got packaged the same way as side gigs. Licorice Pizza looks like a hangout movie, but their “romance” only moves forward when Gary invents the next project. That’s the deal flow. And that’s why it stings. Anderson’s not nostalgic for the ‘70s here. He’s showing us what it felt like to look for connection in an era where everyone was already busy trying to IPO their personality.

In 2010s, Anderson was filming rituals until miracles looked like routine. Stitch, feed, charm, protect—repeat—became a cultural operating manual. Watching Phantom Thread and Licorice Pizza together gives you a taxonomy of that manual: who controls the stitch, who markets the feed, and how charm buys access to both. In the end, both films render the technologies of interpersonal governance legible, and they show how the twenty-first-century market learned to harvest intimacy, convert it into performative labor, and sell the nostalgia back as proof of a life well-lived.

II. now: the good doctor pta

Anderson’s diagnosis of America has finally turned terminal.

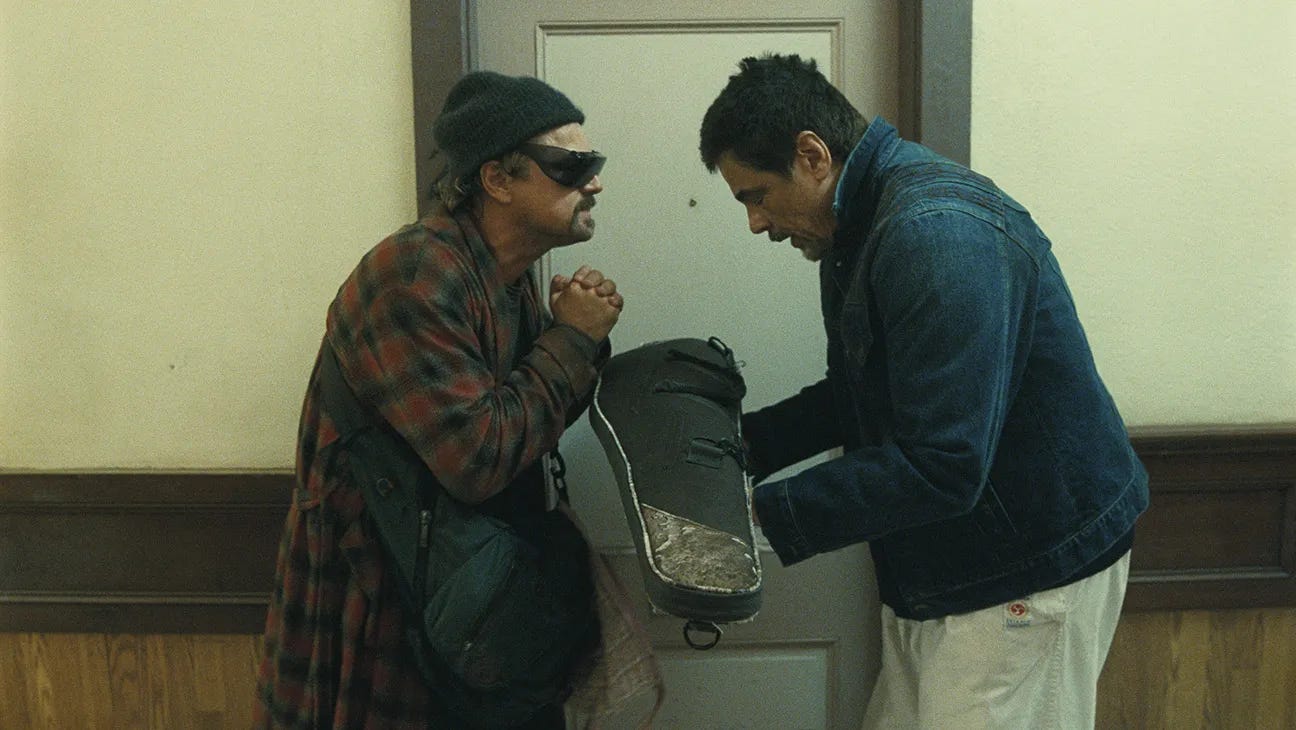

After decades of making us work for his meaning, Anderson has ditched the subtlety and gone full battle axe to America’s jugular with One Battle After Another. Did you think you were getting metaphors about the American condition? Fuck you, here’s an actual detention center with actual children in cages. Thought you’d get another dreamy meditation on power? Nope, here’s Sean Penn as a fascist military creep literally masturbating to protestors getting tear-gassed.

The editing reinforces this collapse of distance. Whereas Anderson once let scenes breathe with languid pacing, One Battle After Another cuts like a racing heart monitor. The film’s rhythm mimics social media’s disjointed attention span, our collective inability to process trauma before the next crisis arrives. A border raid cuts directly to a child separation cuts directly to a protest cuts directly to a military crackdown. It’s overwhelming by design.

Why the sudden urgency? Because we’ve reached stage four.

DiCaprio’s Bob Ferguson represents Anderson’s most radical evolution as diagnostician. Unlike previous PTA protagonists whose delusions drove the narrative, Ferguson’s paranoia turns out to be the only rational response to reality. His bug-out bags, radio jammers, and constant fear of surveillance, presented initially as symptoms of post-traumatic stress, gradually reveal themselves as appropriate adaptations to America’s surveillance state. It’s everyone else who’s delusional.

This inversion marks Anderson’s most damning diagnosis yet: it’s not that paranoid people see threats that don’t exist. It’s that comfortable people don’t see threats that do. The mad prophet screaming on the corner isn’t hallucinating.

He’s the only one paying attention.

Quite striking is Anderson’s treatment of political violence. His previous films portrayed brutality as aberrant—Daniel Plainview bludgeoning a man with a bowling pin, Barry Egan destroying a bathroom in rage. These were ruptures in social fabric, shocking in their deviation from norm. In this film, violence is ambient. Tear gas hangs in air like weather. Police batons swing with bureaucratic regularity. The detention center runs with institutional efficiency. This is routine.

The disease has normalized.

And it reveals itself most clearly in the twisted relationship between Lockjaw and resistance fighter Perfidia. Sean Penn delivers a performance I’m sad to report is pretty freaking great—his military commander isn’t a frothing tyrant but a bureaucrat with a badge who gets aroused by domination. When Teyana Taylor’s Perfidia (in the film’s standout performance) humiliates him, his pursuit transforms from professional to pathological. Anderson frames their cat-and-mouse game as perverse courtship, which exposes fascism’s libidinal core: it wants to own resistance, study it, get off on it.

Power hunts what threatens it not to destroy but to consume.

If Anderson was merely documenting America’s descent, One Battle After Another would be unbearable (see: Eddington). But his diagnostic skills come with an unexpected prescription. The film’s heart—Bob’s relationship with his daughter Willa—offers something I didn’t quite expect: a treatment plan. Their dynamic isn’t sentimental parent-child bonding but a case study in intergenerational resistance. Bob’s revolution failed because it was built on rage without infrastructure. Willa’s approach, using her father’s tactical knowledge while rejecting his nihilism, suggests a new pathway.

Hope.

“I have four kids. I’d better be fucking optimistic,” Anderson told The Rolling Stone. As a father of four himself, he can’t indulge in doomer fatalism or revolutionary fantasy.

Which is the ultimate evolution of Anderson as diagnostician. His earlier films told us America was sick. One Battle After Another acknowledges it’s dying, but insists the manner of its death still matters. It’s hospice care as resistance strategy. It’s making the pain meaningful. It’s refusing to go gentle, even when the prognosis is grim.

And better yet, terminal doesn’t mean finished. Even dying systems can fight back. Even failed revolutions contain seeds for what comes next. Their tensions must be lived through, one battle after another, until something new emerges from the struggle. I walked out of the theater feeling something I hadn’t felt for a very long time: not optimism exactly, but possibility. The doctor isn’t promising a cure but he’s reminding us that how we respond to the diagnosis is still entirely up to us.

A reader shoutout

Congrats to Sophie Blackshaw for winning the book Paul Thomas Anderson: Masterworks from my last giveaway. I’ve DMed you 🫶🏻

A final note for people with taste 🫦

While the internet’s prioritizing hot takes and SEO-optimized nothingness, I’m here building a sanctuary for people who believe film and television criticism can be thoughtful, accessible and fun all at once.

For the price of a truly mediocre sandwich, consider joining the resistance with a paid subscription – it keeps independent film writing alive and the algorithms at bay.

Plus, you’ll get exclusive access to After Credits, my monthly handpicked selection of films & tv shows that will stop you from doomscrolling Netflix AND exclusive access to my more personal reflections.

Now go forth and raise those standards, darling.

- Sophie x

One Battle After Another also confirms PTA's love for commercial movies where one plot point was his riff on Mission: Impossible. The entire gag where Bob is on the phone trying to get the rendezvous point but cannot remember the password was apparently inspired by PTA thinking, "What would happen if Ethan Hunt forgot the code words used in spy exchanges?"

Another wonderful piece of writing, Sophie. You made me want to go back and rewatch all the PTA films I've already seen-- which is nearly all of them-- in anticipation of seeing his latest one. On another note, I don't think it matters what passport those of us in the West have in our pockets these days-- we're all just immigrants waiting to be cast out or lemmings marching in formation towards the cliff's edge.