on films refusing to say goodbye (and attachment issues)

Peter Jackson's refusal to end Return of the King taught me everything about why some movies won't die—and why I can't finish anything either.

I first recognized my compulsive relationship with false endings during a midnight screening of Return of the King. The film had reached its emotional zenith, Aragorn was crowned, the hobbits returned to the Shire, and I'd already mentally composed my AOL Instant Messenger away message to capture how devastated-yet-fulfilled I felt. Then Peter Jackson delivered another ending. And another. And another. By the time Frodo boarded that freaking boat for the Undying Lands, my bladder had become its own character arc, more urgent and compelling than anything happening onscreen.

There's nothing quite like the unique psychological test of a false ending.

Sometimes it's an extra scene. Sometimes it's an entire additional act that feels like a film hijacking. You've already decided this movie gets 4.5 stars on Letterboxd, and suddenly you're held hostage for 20 more minutes while the filmmaker desperately tries to explain the metaphor you already understood. There was even a great parody of this in The Studio’s third episode guest starring Ron Howard and Anthony Mackie.

I've been thinking about this phenomenon again ever since my recent rewatch of Cast Away. The movie gives us that perfect, heart-wrenching scene of Tom Hanks at the crossroads after returning Helen Hunt's package. He stands there, alone at the junction of four empty roads stretching into the unknown distance, his future literally unmapped. It's cinema at its most eloquent. A visual poem about the terrifying freedom of starting over.

And then the movie serves up one more scene where he meets the artist who made the wings package, a woman who is so obviously being set up as a potential love interest that you can practically hear the screenwriter's pen scratching out "LOVE INTEREST???" in the margins of the script.

Nonetheless, sometimes these false endings are brilliant. Sometimes they transform a good movie into pure excellence by subverting our expectations about narrative itself. Psycho pulls off perhaps the greatest false ending in cinema history by appearing to conclude the story of Marion Crane's theft, only to murder her and launch into an entirely different and more terrifying tale.

What intrigues me is that razor-thin line between excellence and indulgence. When is a false ending a stroke of genius that challenges our understanding of storytelling conventions? And when is it just a filmmaker who couldn't bear to kill their darlings during the editing process?

As I've sat with this question, I've started to notice how my response to these cinematic moments of hesitation mirrors my reaction to similar patterns in my own life. Last week, I finally replied to the 5 collaboration requests that had been sitting in my inbox for probably 37 days, crafting the perfect "so sorry for the delay" opener. I currently have 11 essay drafts open in separate tabs, all between 60-90% complete, because finishing means publishing, and publishing means judgment. My Instagram account has been in a perpetual state of "taking a break to focus on my newsletter" for so long that the break has become the status quo. Even my London flat exists in two states simultaneously. Half carefully decorated, half still arranged as if I might suddenly need to relocate back to Athens at a moment's notice.

So yes, let’s just say, I'm confronting my own reflection here.

For what it’s worth, I don't think I'm alone in this pathology. Which is why over the next few paragraphs, I'm going to dig into the psychology behind why some false endings leave us breathless while others leave us checking our watches. I'll examine how these extended conclusions can either elevate a film or completely undermine what came before. And as someone obsessed with endings (gestures vaguely at newsletter name), I'm endlessly fascinated by what these narrative fake-outs reveal about our complicated relationship with saying goodbye — both to the stories we love and to all the things that surrounds us.

For this exploration, I'm joined by writer/director jen harrington, a DGA/WGA filmmaker with both the academic background (BFA and MFA film degrees from UCLA and USC) and the hands-on experience (multiple script sales and distributed films) to help us decode these structural choices from a screenwriter's perspective.

She’s also currently running a wonderful INSPIRED screenwriting competition you don’t want to miss.

the anatomy of false endings

The false ending exists in that precarious narrative territory where structure becomes manipulation. Unlike a plot twist, which reorients our understanding of what we've seen, the false ending plays specifically with our sense of narrative completion. We want structure. We want meaning. We want the assurance that the random events of life can be shaped into something with purpose. When a film refuses this comfort, it reminds us uncomfortably of real life—where Monday follows Sunday with brutal indifference to whether your weekend provided any resolution.

Films like David Fincher's Gone Girl exemplify the "sequel bait" false ending. That moment when Amy returns home covered in blood, triggering what feels like a resolution, only for Fincher to continue methodically unraveling his characters for another act. The audience's collective exhale is deliberate. We're meant to feel the temporary relief of closure before being dragged back into the nightmare.

Denis Villeneuve's Prisoners pulls this same trick with even more cruelty. We watch Jake Gyllenhaal's Detective Loki discover the hidden pit where Hugh Jackman's desperate father has been buried alive. The pieces click. The mystery solved. We exhale. And then instead of showing us the rescue, the moment we've earned after two-plus hours of rain-soaked emotional torture, Villeneuve simply lets Loki hear a whistle. Cut to black. Roll credits. What kind of monster ends a movie there, you ask? The kind who understands that our imagination will torment us more than any resolution ever could. We walk out of the theater not just wondering if Jackman lives, but imagining entire future timelines: his psychological recovery, the family attempting to rebuild, the ripple effects of trauma that would define a theoretical Prisoners 2 that Villeneuve never intended to make.

Then we have what might be called the "director couldn't let go" ending. Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now would've had different effect if it wrapped after Kurtz's assassination intercut with that ritual slaughter, just fading to black as the boat disappears. Instead, we get Martin Sheen's departure scene. A respectable choice, sure, but Coppola really needed one last hit of his own creation before letting us all move on.

For a truly baffling case of directorial attachment issues, we’ve also got to look at Darren Aronofsky's mother! The film builds to a literal apocalypse: the house explodes, Jennifer Lawrence burns to ash, everything is destroyed. Game over, point made. But Aronofsky tacks on another scene where Javier Bardem extracts a crystal from Lawrence's charred remains and the cycle begins again with a new woman. Aronofsky got to the register with his metaphor, paid in full, then couldn't resist grabbing one more item on the way out. This refusal to settle for a single ending reveals a specific impermanent fear of ours: that if we truly conclude something, we'll have nothing left to say.

The "epilogue that ruins everything" false endings perhaps find their ultimate expression in I Am Legend (2007), where Will Smith's character heroically sacrifices himself to save humanity. This saccharine epilogue completely betrays the film's built-in moral ambiguity—the revelation that he had become the monster in this new world. The existence of a vastly superior alternate ending (where Neville realizes the Darkseekers have consciousness) only highlights how thoroughly the theatrical epilogue misunderstands its own story.

Similarly, Sunshine (Danny Boyle) delivers a tightly wound space thriller until its final act, when it abruptly transforms into a slasher film with a sun-maddened antagonist. The false ending isn't just an additional scene but sometimes an aesthetic rupture—a shift in genre that betrays the film's initial contract with its audience.

On the contrary, the false endings that truly captivate me are those that use our expectation of closure against us. I call them the "subverting expectations" endings. Wong Kar-wai's Chungking Express shifts to an entirely new narrative halfway through the film, creating a structural rupture that somehow makes both stories more resonant. Michael Haneke's Caché concludes with a seemingly innocuous long shot where two characters meet briefly in the background—so subtle many viewers miss it entirely. This anti-ending refuses catharsis and instead implicates the viewer in the same voyeuristic position as the film's protagonists. We're left unsettled, uncertain, denied the comfort of resolution. Exactly as Haneke intends.

Paul Thomas Anderson's The Master builds toward a confrontation between its central characters that never materializes in the expected form, instead offering a dreamlike denouement that suggests psychological rather than narrative resolution. The film refuses to give us a definite answer, leaving us with an image rather than an answer. Sometimes this is narrative courage (intentional ambition), other times it’s narrative cowardice (unintentional ambiguity). But in this case, the willingness to end with a question mark rather than a period is powerful (also see: all David Lynch films).

when the false ending works

SOPHIE: Over to you, Jen. What are some examples where that "one more scene" or that narrative fake-out was essential to the story's impact rather than diluting it?

JEN: First, I have a general theory about the ‘false ending’ phenomenon: it’s actually inherent to the way we structure screenplays as writers.

In a traditional three act structure, often the story can be further broken down into sequences. The first act contains sequences 1 and 2, the second act has 3, 4, 5 and 6, and the third act has sequences 7 and 8. Sequence 7 typically contains the climax of the film and ends with the resolution. It is also where any finally twist in the story will be revealed. Sequence 8 is the aftermath, the wrap-up, the establishing of the new status quo.

So, In this sense, we FEEL an ending when sequence 7 finishes, because the main conflict, that we have followed through the entire film, has now resolved or the final piece of the puzzle has been revealed. We’ve held our breath for over an hour and now we can exhale. What a writer/filmmaker chooses to do with sequence 8 is where we can find ourselves in movies that seem to want to epilogue us to death, or in establishing a new status quo, end up trying to set up an entirely new story.

As a writer, I’ve always found this part of the script exceptionally tricky. How you leave your audience feeling is so important - any missteps can undo all the trust you have built with them to that point. Even something so slight as pushing them past their bladder limit can color their whole experience of the film (see Return of the King - I know someone who legit pissed their pants in the theater, it’s not just urban legend folks).

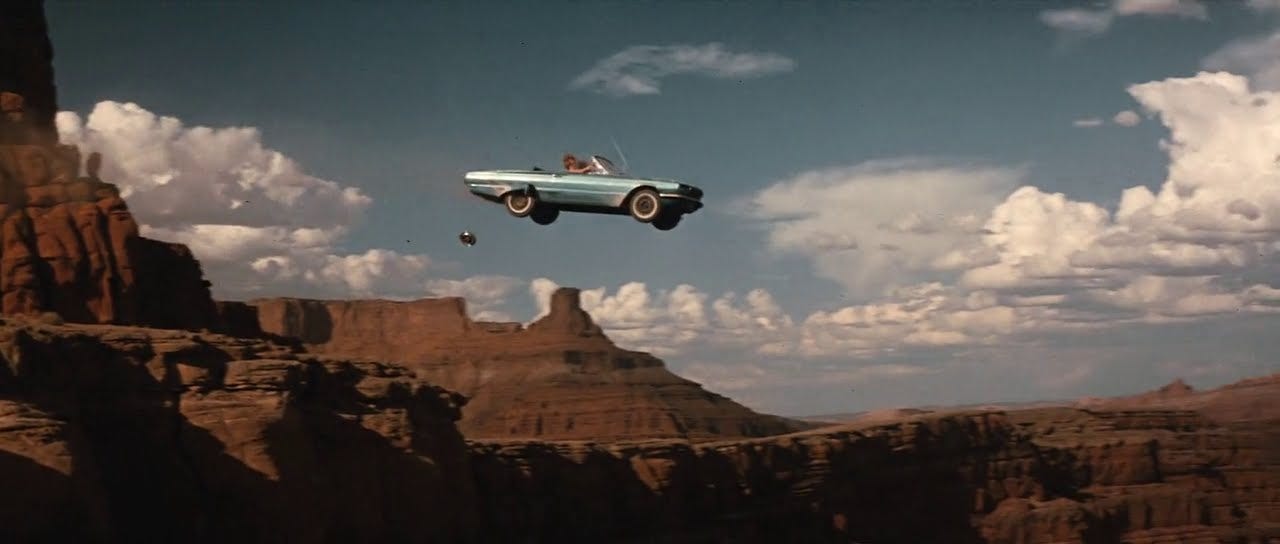

I think this is why I tend to favor films whose last sequence is as brief as possible, if it’s there at all. Less of a chance to spoil the mood. Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid, with that freeze frame in the shoot out, Thelma and Louise, with them driving their car off the cliff - both these films end with the end of sequence 7. There is no wrap-up, the story is left to finish in the viewers minds.

Or, take The Graduate, whose sequence 8 consists wholly of one shot: the young couple on the bus. The epilogue is for us to infer, the film being more interested in concluding with a feeling rather than tying up threads.

However, don’t we love to have those threads tied? (I mean, the popularity of Colombo alone seems to be proof). I’ll admit, there is satisfaction in feeling like you KNOW what happens after the credits roll and the lights come on. No ambiguity. An oft repeated gimmick, the ‘Where are they now’ montage at an end of the film, famously done in Animal House, works because it gives us that extra little dopamine hit of having all the answers. Nothing left undone. It’s all tied up in a neat little bow, and doesn’t that feel good?

So, back to your question, Sophie. When did the filmmaker nail that last sequence?

Seeing Henry Hill stranded in the suburbs at the end of Goodfellas, perfect.

The message Lady Bird leaves her mom at the end of Lady Bird completes the narrative by completing her character arc.

Even though I’m one of the few people who doesn’t drool in admiration over The Shawshank Redemption, even I have to admit it’s so fun to have Red and Andy reunite in the end.

Movies like The Natural, The Hunger Games, or the last Harry Potter movie, all end with a moving, albeit not particularly original, ‘everything’s going to be okay’ scene. Robert Redford is playing catch with his son, Katniss and Peeta have their own kids, Harry is sending his off to Hogwarts. These postscripts, despite totally pandering to the audience’s desire for that neat bow, succeed in the fact that they do, in fact, feel good. The story feels complete. No unanswered questions. My favorite of this type of epilogue comes from Shaun of the Dead. Seeing Ed is still ‘alive-ish’ and in the shed playing video games feels like the cherry on top the sundae.

I’d argue the ending of There Will Be Blood (and I do mean argue since I know plenty of people despise the last sequence of this film) is a fantastically bold departure from the story we have watched to that point… and yet, it also feels like it is showing us the truest outcome there ever could have been for Daniel Plainview. In that last bonkers melée, we are shown the inevitable result of Daniel’s fight with himself and the world around him in the most gloriously over the top and non-sensical way possible.

SOPHIE: I adore the final scene of There Will Be Blood.

when it doesn’t

SOPHIE: So you've seen the industry from both sides of the camera. What are some films where you think those additional scenes after what could have been a perfect ending actually damaged the movie?

JEN: Well, as I just mentioned, for a lot of people There Will Be Blood would be an example of an ending that didn’t work, and I acknowledge, it’s not going to be for everyone. That said, Paul Thomas Anderson took a huge swing and didn’t really care if you liked it or not, and that, in itself, to me, seems deserving of praise.

Another movie I feel like could be on both lists is The Departed. First, let’s get this out of the way, the final shot of the rat going across the screen made me actually yell out loud, ‘NO!’ in the theater. I hated it so much and for a long time felt like it had ruined the whole movie. Here was this tragic story with great performances that was concluded with the most obvious on the nose metaphor I’d ever seen (I mean, not ever, but when I’m emotional I’m prone to hyperbole).

However, for the sake of this post I’ve been able to look past the lamest shot of all time and examine the rest of the ending. And, although it’s everything you absolutely ever wanted to have happen, Matt Damon’s character finally getting what he deserves… it feels like wish fulfillment. What seems like would have really happened in the world of this story is that Leo would die and no one would ever know who he really was, and Matt would go on to live a nice life. Marty didn’t want us to have live with that, and while I thank him, I do feel like ultimately this is a happy ending slapped on a tragedy.

I felt similarly about the ending of Promising Young Woman. An ending where everyone got their just desserts… felt like a silly fantasy. What had been a disturbing portrayal of a woman coming to terms with how the world treats/sees women and what, if anything, she could do about it, turned into a revenge fantasy that seemed to undo so much of the sharp storytelling that had come before it.

Last, you can’t leave out the O.G. ‘one scene too far’ ending: the ‘it was all a dream’ epilogue which hardly anyone pulls off outside of Mullholland Drive and The Bob Newhart Show. Case in point: The Devil’s Advocate which almost is apologizing for the ridiculous movie we just watched - it’s like it’s saying, ‘Actually? Our bad. Nevermind. Let’s pretend this never happened, shall we?”

SOPHIE: I loathe the final scene of Promising Young Woman.

reflecting on our own false endings

So why do some false endings work while others don’t? After dissecting all these cinematic farewells, the answer reveals itself: The false endings that stay with us are those brave enough to acknowledge that endings rarely give us what we want—neat resolution, complete answers, the satisfaction of everything making perfect sense. Instead, they give us what we need: meaning, even in its tangled incompleteness. The ones that frustrate us are those that extend the story not out of artistic necessity but out of fear. Fear of audience disappointment, fear of finality, fear of commitment to a single vision (this speaks to artists in particular).

This fear mirrors something deeply human in all of us. Look around your home right now. That stack of books you will certainly ‘read one day’. The clothes that won’t fit you since 2019. Your abandoned projects, each one a testament to your own fear of failure or, perhaps more accurately, your fear of being finished. The text message from that ‘friend’ drifting into a hazy "we should catch up sometime," when there is an unspoken understanding that neither of you are willing to invest the emotional labor required for true closure.

You keep these things for a reason.

The Portuguese have a word, saudade, for the presence of absence—the emotional experience of missing something you once had. Perhaps what we’re really avoiding with our perpetual false endings (whether we’re screenwriters or normies) is the saudade that true endings generate. If we never definitively say no to collaborations, if we never mark our work as "complete," if we never fully commit to our temporary places as home, we can maintain our delulu notion that all doors remain open. Søren Kierkegaard wrote of the "dizziness of freedom," that vertigo we experience when faced with limitless choice. That’s the terror that whispers:

As long as I hold onto this, I maintain all future possibilities. I find a seductive illusion of control in maintaining this constant state of narrative possibility. I become trapped in a perpetual state of narrative adolescence, forever postponing the moment of maturity, of acceptance, of closure.

Sadly, for many of us, ordinary disposal is a mental achievement. To look at something and say "this has served its purpose, and now I can let it go" requires a certain psychological health. It demands that we have enough confidence in who we are to know that our identities aren't contingent on these external anchors. But this kind of disposal becomes exponentially harder when our sense of self was formed through loss rather than security. Some of us struggle with letting go because our earliest experiences taught us that things disappear without warning or permission. The inability to end things properly often stems from having had endings imposed upon us when we were too young to understand or consent.

In other words, behind our reluctance to end things properly often lies an ancient wound.

Perhaps then, the most compassionate question we can ask ourselves in these situations isn't "Why can't I let go?" but ‘When I was younger, was there something I lost too suddenly? Was it some dream I had to abandon before I was ready? Some goodbye I never got to say?’.

Because here's the truth about meaningful endings, in films and in life: when stories refuse to end, when they dangle endlessly before us, they become weightless, ephemeral, interchangeable commodities to be consumed and discarded without leaving any lasting impact. When Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind ends with Joel and Clementine deciding to try again despite knowing their relationship will likely fail, the film empowers us with the knowledge that meaningful experience is worth having even when – especially when – it must eventually end. The best screenwriters know this intuitively.

I believe it's time we learn from the best endings in cinema not by extending our stories indefinitely, but by making each moment count precisely because it cannot last forever. What would it mean to embrace the power of a true ending, not as a failure or a limitation, but as the very thing that gives our stories, their shape, meaning and power to move us?

After all, the most beautiful sentence in storytelling has always been the simplest:

The End.

A final note for people with taste 🫦

While the internet's prioritizing hot takes and SEO-optimized nothingness, I’m here building a sanctuary for people who believe film and television criticism can be thoughtful, accessible and fun all at once.

For the price of a truly mediocre sandwich, consider joining the resistance with a paid subscription – it keeps independent film writing alive and the algorithms at bay.

Plus, you'll get exclusive access to After Credits, my monthly handpicked selection of films & tv shows that will stop you from doomscrolling Netflix AND exclusive access to my more personal posts.

Want me to write an essay on your favorite film or TV show? Upgrade to Founding Member and you’ll enjoy this very special perk ✨

Now go forth and raise those standards, darling.

- Sophie x

This all seriously resonates. “Return of the King” ending has been my filmmaking collective’s shorthand for “didn’t know when to end it” for years — I’m relieved to see we aren’t alone.

As to the “why” and psychological underpinnings of fear of finishing things, this strikes a chord, as well. As a kid, I couldn’t finish food. Not a sandwich, banana, apple, anything. I still don’t like doing it. That last bite of anything only gets eaten off my plate if I’m trying to not offend the chef.

So it shouldn’t be a surprise the deciding factor in me once choosing to make a film was that the script had a beautiful bold fuck you non-ending. Another film I made has a “it was all a simulation” ending, which I actually re-wrote from something originally more grounded in the film’s reality.

In fact, I just got off the phone an hour ago with a director whose movie I’m producing currently, discussing possibly reshooting the ending of a film we are close to locking picture on, or throwing out the ending entirely! Just straight up cutting to black at the end of sequence 7. And to be honest, I find that idea incredibly thrilling.

Endings are hard! Painstakingly, brutally, teeth pullingly hard.

If I spent a decade or more of my life making the LOTR trilogy, I’d probably end it 9 times, too!

I will be sharing this with every filmmaker friend who is currently editing something — and will reference as I’m writing my next one. And even then, I’ll still change it in the edit. Isn’t that why we make films? To command the things on screen we can’t control in life? Like death, and other forced endings?

The "extra ending" always struck me as a sense of distrust. Particularly in films where there's a moral message, but one you'd have to decide for yourself. Something like "Flight" qualifies, where I figured Denzel would find the mini bar the night before his big hearing, and then you'd cut to black, wondering if he did the right thing in the end, or if you would have in his place. Then there's the whole bit where they find him the next morning, dress him up, and try to get him to the hearing. Again, there's the suspense -- is he going to get away with it, or is he going to do the right thing? And then that ending arrives in BIG CAPITAL LETTERS because Zemeckis just did not trust us to mentally make the right decision for this character, he didn't trust our morals as an audience at all.

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com