why does August make me so fucking sad?

August brings back that feeling of deflated fantasy every single year.

I watched The Virgin Suicides for the first time when I was seventeen, sprawled across my childhood bedroom floor, the rough carpet fibers pressing patterns into my bare legs, laptop balanced precariously on a stack of philosophy textbooks I'd borrowed from the library but never actually cracked open. The screen's blue glow made everything in my room look underwater—the unmade bed, the clothes draped over my desk chair like abandoned costumes. The film opens with boys obsessing over girls they'll never really know, and ends with those same boys, now middle-aged, still trying to solve a mystery that was never meant to be solved.

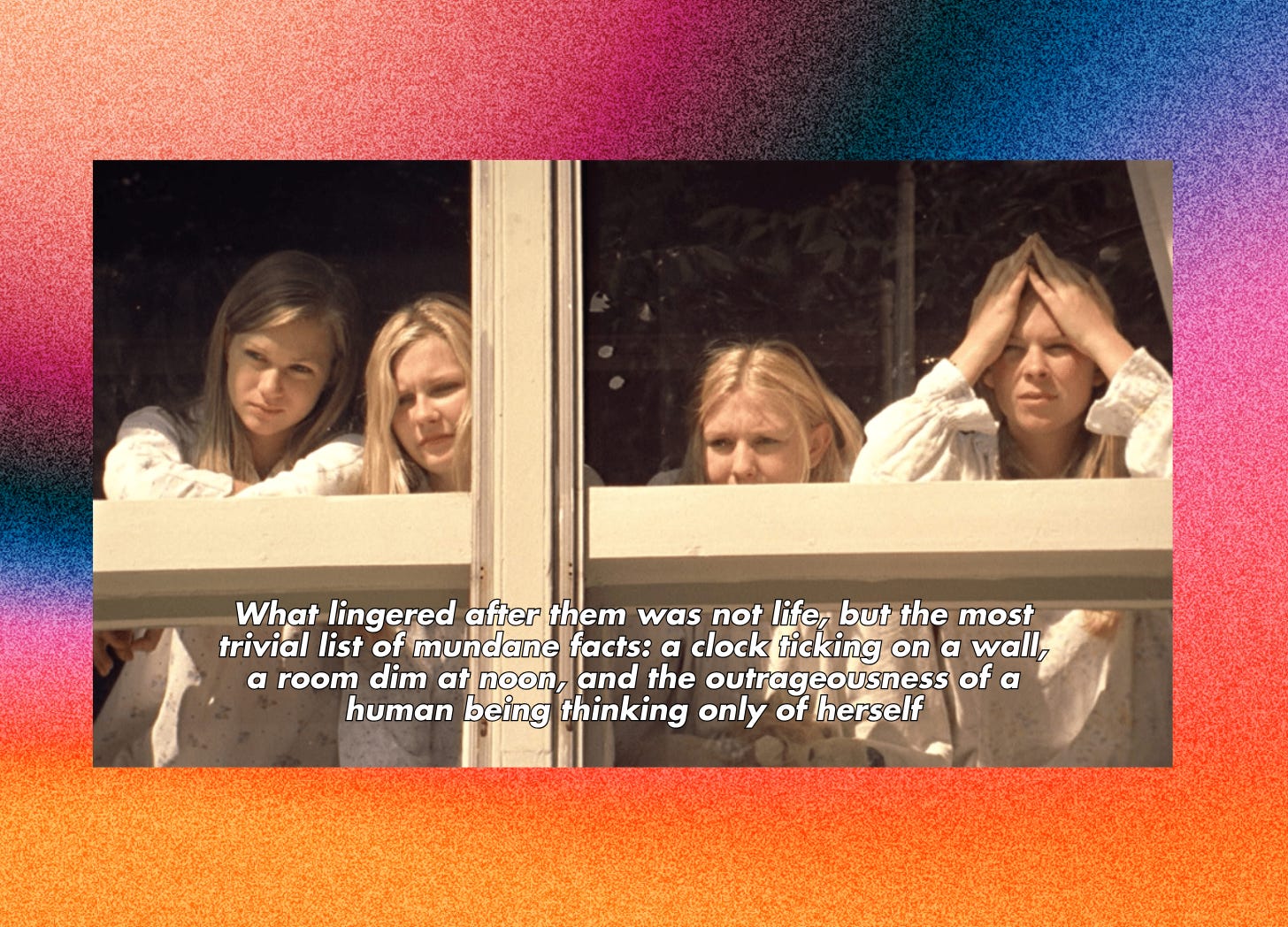

Towards the end of the film, the boys show up at the Lisbon house front yard thinking they're about to orchestrate the great escape. They call the girls on the phone and play a record for them over the receiver, a silent signal that they are waiting outside. For thirty seconds, they allow themselves to imagine it: rescuing these ethereal creatures, becoming the heroes of their own story, conjuring the sort of transcendence that feels like it should just happen naturally when you're young and beautiful and tragic.

Except nobody comes downstairs.

The film holds on their faces as the fantasy disintegrates in real time. You watch them realize that the girls aren't coming, that their carefully planned rescue mission has become just another evening of teenage boys with nowhere special to go. Coppola won't cut away or spare you the awkwardness. She makes you endure every second of their deflation, the slow collapse of their cinematic expectations into suburban reality. And still they wait, because admitting defeat means driving home to their own bedrooms, their own ordinary Thursday nights, their own unremarkable suburban lives.

I think of the movie as being feminine, but it’s true, it is from the boys’ point of view, imagining them as these kind of ethereal creatures and kind of really going with that.

Sofia Coppola (The Playlist)

Every August brings me back to that front yard. It creeps up on me — the melancholic density that settles in your chest when the air turns thick and the light starts slanting differently and you realize, with startling clarity, that nobody is coming to save you from ordinary time.

I felt the loss of that infrastructure for the first time at nineteen, living back home in Athens during my first uni summer break. The August heat made everything shimmer and blur, the air so thick it felt like breathing through wet cotton. I'd wake up every morning to the sound of my neighbor's television bleeding through paper-thin walls, the synthetic laugh track from some morning show mixing with the distant hum of air conditioning units working overtime.

The day stretched ahead of me like an empty stage. No one was directing the show anymore. No one was saying "today we're going to the beach" or "tonight we're having a barbecue" or "put on something nice, we're going somewhere special." Even rebellion felt organized—sneaking out to meet friends at predetermined locations, breaking rules that had been set specifically so we could discover the thrill of breaking them.

David Foster Wallace (unsurprisingly) wrote about this—how adult freedom is actually the "banal platitudes of the day-to-day trenches of adult existence." How choosing what to think about, how to construct meaning, what to pay attention to, becomes this exhausting daily burden that other adults don’t warn you about. You spend your childhood being told you can't wait to grow up and make your own decisions, and then suddenly you're standing in your kitchen on a random Tuesday afternoon in August, barefoot on cold linoleum, staring at the refrigerator's contents like they might rearrange themselves into a plan. The fluorescent light buzzes overhead, casting everything in that sickly institutional pallor that makes even fresh fruit look depressing.

Time. Adulthood grants you that temporal sovereignty that your childhood never offered. Not the structured time of school days, but a vast, empty expanse of hours that are all your own. August freedom operates as a merciless loan shark—you're given this unspendable coin, and you have no idea what to buy with it. You can't purchase spontaneity. You can't buy back the infrastructure of care you once had. So you end up simply holding it, watching it accumulate and waste away, all while the world tells you that time is the most valuable thing you own.

But the most perverse aspect is that August still carries all the mythological weight of transformation. It's still supposed to be the month of last chances, final kisses, dramatic revelations before everything changes again in September. Summer movies are released in August because it's when we're meant to feel most alive, most willing to believe in magic. But when you're responsible for creating that magic yourself, when there's no external force orchestrating these meaningful moments, August becomes the month where you confront your own incapacity for alchemical transformation.

I've grown disturbingly attuned to this phenomenon this past week. Scrolling through Stories of elaborate birthday parties people planned for themselves, travel itineraries researched and booked and executed solo, dinner reservations made with the desperate hope that choosing the right restaurant might somehow make the evening feel special. We're all performing this frantic self-curation, trying to become the directors of our own coming-of-age films, but missing the essential ingredient: someone else believing in our story enough to help write it.

This existential displacement feels so disorienting because we've moved from a world of being seen to a world of looking. It’s hard not to think of John Berger's work when I write about this and how he spent the 1970s dismantling the way we think about images and attention. In "Ways of Seeing," he argued that reproduction fundamentally changes what images mean—that when you take a sight and turn it into an image, you strip it from its original context and add subjective value. But more than that, he showed how the act of looking is always political. Who gets to look? Who is meant to be looked at?

Berger famously wrote that "men act while women appear," meaning men get to move through the world with agency while women are constantly monitoring their self-presentation, always aware of being watched. But childhood exists as a pre-political sanctuary. Back then, you were held in other people's attention without having to earn it. Your dad noticed you were bored before you even realized it yourself. Your friends' parents automatically included you in their plans. You were seen, not because you performed visibility, but because adults created a web of care that didn't require your participation to function. You could simply inhabit your own existence, and that inhabitation was enough to generate care, attention, wonder.

Now you're trapped in the apparatus of visibility. You conduct reconnaissance on your environment for opportunities, for people who might notice you, for moments that might transform into memories worth keeping. It's the difference between being discovered and trying to be discoverable. Now you have to build that web yourself, thread by thread, and most of the time you're not even sure if anyone's paying attention to the intricate patterns you're weaving.

The terrible mathematics of waiting for rescue is that the longer you do it, the less capable you become of recognizing opportunity when it finally appears. You spend so much time looking for someone to hand you a ready-made adventure that you lose the ability to see raw materials as potential enchantment. A free afternoon becomes dead time instead of possibility. An empty weekend feels like abandonment rather than a blank canvas. You start to resent the people who seem to effortlessly create meaning in their lives, not realizing that what looks effortless is actually the result of small daily choices to architect rather than wait.

Eventually, even when someone does offer to include you, you can't fully receive it because you've forgotten how to be an active participant in your own rescue. You've rehearsed passivity for so long that you've atrophied the musculature required for agency.

Yesterday I was walking through Turnham Green when I saw a mum pushing her daughter on a swing, both of them laughing at some private joke I couldn't hear. The little girl's hair flew behind her in golden ribbons, her legs pumping air as she shouted "higher! higher!". The chains creaked with each arc, and the mother's hands never hesitated—push, step back, push again, an automatic rhythm of care that required no thought, no planning, no desperate googling of "fun activities for children." Someone else was doing the work of orchestrating wonder.

I called my mum as soon as I got home, pacing around my flat with the phone pressed against my ear, the familiar gravitational pull of her voice carrying me back to smaller rooms and simpler problems.

"I've been thinking about when I was little," I said, bypassing any greeting. "Do you remember how you always knew exactly what to do when I was bored?"

She laughed with that laugh she does when she's remembering me as a child—soft and slightly amused, like she's watching old home videos in her head. "You used to get this look on your face. Like you were waiting for something to happen but didn't know what."

"And you'd just... fix it somehow. A trip somewhere, or letting me help with dinner, or calling one of my friends."

"Well, yes. That's what mothers do."

Now that I’m feeling this August restlessness, I have to diagnose it myself, prescribe the cure myself, and administer it myself. I have to be the parent who says "let's pack you some lunch" and the child who gets excited about having their favorite meatballs saved for later. I have to manufacture my own spontaneity, and somehow still be surprised by the results. Hell, I'm producing my own summertime sadness at this point. You have to actively notice when August light gets wistful, remind yourself to feel appropriately melancholy about summer ending, basically become your own Lana Del Rey cover band. Rescue makes you special. Self-rescue just makes you competent.

Those boys were waiting in that front yard for someone to need them badly enough to come downstairs and change their story. They never left because leaving meant admitting they weren't special. That their suburban lives were exactly as mundane as they appeared. That the Lisbon sisters weren't mystical emissaries sent to transform them—they were just girls who died, and it had nothing to do with anyone else's narrative.

In a parallel universe, if I could, I would run to them and tell them: the house is dark. It's always been dark. The infrastructure that once turned empty time into memory, that transformed boredom into adventure, that made your existence feel like a story worth telling—it expires when you stop being someone's child. What you get instead is harder and lonelier and occasionally devastating in its ordinariness. You get to be the curator of whether tonight matters. You get to be responsible for your own August. And yes, most of the time you'll fail. Most evenings will dissolve into nothing. Most summers will pass without the transformation they seemed to promise. But some nights—maybe one night, if you're lucky—you'll forget you had to choose to be here. You'll forget that nobody made this happen but you. And for those thirty seconds, it won't matter that you're your own emergency contact. Because you'll be too busy living to notice who's doing the work.

A final note for people with taste 🫦

While the internet's prioritizing hot takes and SEO-optimized nothingness, I’m building a sanctuary here for people who believe film and television criticism can be thoughtful, accessible and fun all at once.

For the price of a truly mediocre sandwich, consider joining the resistance with a paid subscription – it keeps independent film writing alive and the algorithms at bay.

Plus, you'll get exclusive access to After Credits, my monthly handpicked selection of films & tv shows that will stop you from doomscrolling Netflix AND exclusive access to my more personal posts.

Now go forth and raise those standards, darling.

- Sophie x

The Reader Hotline is open for submissions 📞

I’ve recently introduced the monthly TFS hotline—think of it as a letters-to-the-editor section but for folks with complex feelings about entertainment.

And I’m taking submissions in the following categories:

Plot armor: The show or film that got you through a difficult time.

Spicy take: Your most controversial film opinion that you'll defend with your life.

Reality check: The film or show that completely rewired your brain.

Triggered: When something on screen or in the theater hit you unexpectedly hard.

You can submit via email (sophie@thatfinalscene.com) or voice note for a chance to have your voice featured in an upcoming hotline. Plus, you’ll get 3-month paid subscription to That Final Scene. Bargain!

Yr right, August sucks. This is why Europeans and New York City finance bros flee to beaches, it's literally not worth the trouble.

💯

somewhat adjacent to the august vibe are the films set in summer that have a hold on me, the heat, the need to do something fun, the impending school year about to start. Stand by me. Do the Right Thing. Call me by your name. American Graffiti and kinda Licorice Pizza. Oh and recently DiDi. There's also a Japanese film I saw 25 years or more ago that I've been forever trying to find the name of, it's set partly in summer where a Korean kid living in Japan goes to see his grandparents in the countryside. It's also set in the school year too, there's a romance, a pop concert and a lot of racism towards the Korean kid. The film has a lot of text on screen that I remember being diary entries, flashing cursor and type. I think I'll go check with ChatGPT and see if I can finally find it. ah ok update. it took two tries but it figured it out, the film is All About Lily Chou-Chou by Shunji Iwai. I'm going to rewatch it...finally!