you deserve to be wonderful

This essay contains spoilers for the film The Life of Chuck.

My boyfriend and I don’t always pick the same films, which is one of my favorite things about us. We’ve built a life together, share a home, coordinate our mornings around who gets the bathroom first. We know each other’s coffee orders without asking. But ask us to pick something to watch on a Friday night and suddenly we’re negotiating like diplomats at a treaty signing—and in all honesty, I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Michael gravitates toward films that look like they’ve been dipped in liquid starlight. Give him sleek sci-fi, impeccable production design, frames you could hang in a gallery. Gattaca’s sterile perfection. Ad Astra’s cosmic melancholy. Don’t Worry Darling’s amber-lit fever dream. He wants cinema that feels designed, intentional, beautiful in a way that borders on artifice. Watching him watch these films, the way he leans forward during a perfectly composed shot, is its own kind of pleasure.

I want people talking in rooms.

Give me After Hours’ nocturnal desperation, characters unraveling in real time. Sunset Boulevard’s bitter monologues about faded glory. I want philosophical weight, dialogue that cuts, conversations that reveal something true about being alive. I want words that matter, delivered by people who don’t know how to stop talking even when they should.

We do often meet in the middle. Sometimes it’s Oppenheimer, a three-hour slog we both survived at the cinema, emerging afterward with the shared look of people who’ve just been through something together, even if we’re not entirely sure what. Sometimes finding a film we both love is harder than the actual watching, but that just makes it sweeter when it happens.

Last week we wanted something different. Cozy. Shared. A cheeky takeaway. An evening where you’re both present in the same story, where neither of you is checking your phone or mentally drafting your Letterboxd review.

So I sat there, scrolling through new releases, trying to triangulate between his aesthetic sensibilities and my need for substance. Then I said it out loud, testing how it sounded: The Life of Chuck.

I’ve written about Stephen King before, how his work shaped me, how it gave me a language to connect with my mum when I was young and struggling to find common ground. His writing isn’t always refined or subtle, but it was formative. It taught me how stories could be engines for emotion and how the supernatural could illuminate the achingly ordinary.

I hadn’t read this particular story. But I know King’s rhythms, his ability to find profundity in the everyday, his willingness to get weird and sincere in equal measure. I’d seen the trailer. Heard the reviews were solid. Something about Tom Hiddleston dancing on the streets. Something about life told in reverse, about finding wonder in the mundane, about—well, I wasn’t entirely sure, but it felt right.

I pulled up the trailer on the TV and asked Michael to watch it with me. He sort of watched but half-way through he said: “You know what? I trust you. Let’s just do it.”

We rented it. Poured our Pepsi. Settled in.

And for the next two hours, we watched Chuck Krantz’s life unfold backward, forward, sideways—watched him dance and love and discover and exist in ways that felt impossibly specific and utterly universal.

This is about that film. But it’s also about you, sitting here at the tail end of another year. Maybe you’re bracing for the holidays, for family dinners where someone will ask what you’ve accomplished this year and you’ll feel that familiar pain in your chest. Maybe you’re already making lists of who you’ll become in January. Better, thinner, more successful, finally worth celebrating.

I sat on that sofa carrying all of that weight as well.

Two hours later, thanks to Chuck, I put it down.

the curious case of chuck krantz

The Life of Chuck opens with the world ending. The internet stops working, then the power. Stars begin disappearing from the sky one by one, like someone’s turning off lights in an empty building. People stand in parking lots watching the universe collapse, holding each other, waiting.

Billboards appear everywhere. Highways. Bus stops. Abandoned shopping centers. All featuring the same face: a middle-aged man with kind eyes and an accountant’s posture. The text reads: “Thanks for 39 great years, Chuck.”

Nobody knows who Chuck is. The film doesn’t explain. It rewinds instead, pulling us backward through time to show us who this man was and why his death might matter to the fabric of reality itself.

Nine months before the end, Chuck Krantz is attending a banking conference. He’s unremarkable. A middle manager. The kind of man who’s perfected the art of taking up exactly the amount of space he’s been allotted and no more.

Then he walks outside and hears a busking percussionist named Taylor (also known as The Pocket Queen in real life!) drumming on the street.

The sound doesn’t ask permission. It just reaches into Chuck’s chest and pulls. His briefcase hits the sidewalk. His body starts moving—hips first, then shoulders, then his whole frame giving in to something he hasn’t felt in decades.

Pure, unselfconscious dancing.

Now let me tell you: this is not a man who dances. This is a man who probably apologizes when he sneezes too loud. But here he is, losing his entire body to a street drummer in the middle of a sunny afternoon while people in lanyards walk past trying not to stare.

A woman stops to watch. Janice. She’s having the worst day of her life. Her boyfriend just dumped her via text, mascara doing that thing where it migrates south—and she sees this accountant dancing like nobody’s watching except everybody’s watching and she thinks: you know what? Fuck it.

She drops her purse next to his briefcase and joins him.

This is how revolutions start. With two strangers deciding that drums are more important than dignity. More people stop. Some pull out phones. Some just watch. A few join in, tentative at first, then fully committed to this strange street miracle.

When Taylor stops drumming, reality floods back in. They’re standing on a sidewalk, breathing hard, looking at each other like people waking up from the same dream. Later, Taylor suggests they split the busking money. They reluctantly agree. They hug. They walk away in different directions, carrying this moment in their pockets like a secret.

The world was made just for that, Chuck will think later. Just for that.

The film keeps rewinding. Back to Chuck’s childhood, to the Victorian house where he lived with his grandparents after his parents died. His grandmother taught him to dance in the living room. His grandfather Albie—bitter, sardonic, drowning in whiskey after losing his son—had one rule: Chuck could never enter the cupola, the locked attic room at the top of the house. “It’s full of ghosts,” Albie told him. “People I saw before they died.”

Albie had looked into that room and seen the future. It terrified him. Albie is a type I know too well: the man who allows himself to be paralyzed by the cosmic knowledge that the script is already finalized. He occupies a house that is literally rotting around him, and he just waits. He shrinks. He becomes a hollowed-out shadow, a prisoner of the interim, convinced that whatever he does now, the narrative is already determined. The years between disaster and resolution, the quiet domestic blur, become a form of slow, self-inflicted erasure.

When Albie dies, teenage Chuck inherits the house and the cupola key. He climbs those stairs. He opens the door. And he sees it: himself, decades older, in a hospital bed. Dying at 39.

Seventeen years old, standing in an attic, staring at your own corpse. Happy fucking birthday, Chuck.

chuck contains multitudes

The film doesn’t show us his face in that moment, which is probably for the best because I can’t imagine what expression you’d make discovering you’ve got twenty-two years left. Do you laugh? Cry? Immediately start a retirement fund? I’d probably just stand there doing that thing where you refresh your bank account app over and over hoping the numbers change.

But Chuck doesn’t do any of that. Years earlier, his teacher Ms. Richards had placed her hands on either side of young Chuck’s head in class. “What’s between my hands?” she asked. Chuck guessed his brain, his skull. She smiled and told him no—what’s between her hands is an entire universe. Every person he’ll meet, every moment he’ll experience, every memory he’ll collect. She was teaching him about Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself”—the line “I contain multitudes.” Your life, she told him, is a world.

Standing in that cupola, staring at his death, Chuck remembers. And he affirms something to himself that changes his entire worldview:

“I am wonderful. I deserve to be wonderful. And I contain multitudes.”

After looking at his ending, Chuck decided the middle still mattered. The film cuts away and when we see him again, years later, he’s dancing on the street like a man wanting to still fill his world with people and ecstatic moments and joy and love. Most of us never get to see inside our own cupola. We don’t know the date, the method, the hospital room number. We live as though time is infinite, as though we can afford to spend years preparing to deserve the life we’re already living. Chuck knew better. He had the information we’re all too terrified to seek: This is finite. This ends. The question isn’t whether you’re good enough to be here. The question is what you’re going to do with the time you have left.

There’s an odd type of paralysis that comes from knowing too much. Albie had it. Why bother repairing the porch when you know the house burns down? Why dance when you know the music stops?

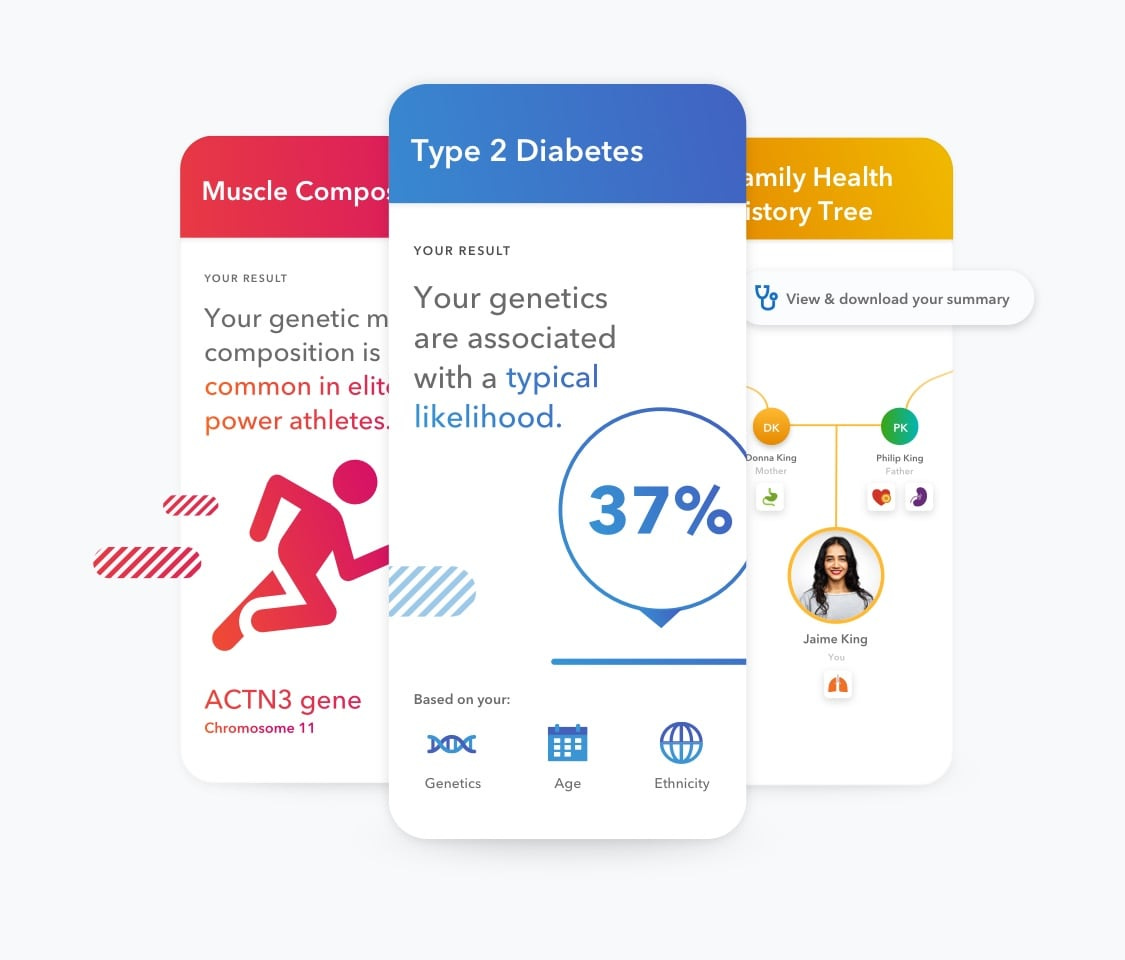

I can sometimes feel that paralysis in me because we live in the age of the cupola. 23andMe tells you your genetic predispositions. Your Oura ring tracks your sleep debt. Your therapy app sends you notifications about your attachment style. We’ve built an entire economy around looking into the future and seeing all the ways we’re going to fail.

And what do we do with that information? We make plans. We optimize. We create elaborate systems to prevent the inevitable. We become Albie, drinking ourselves numb on data, convinced that if we just track enough variables, we can avoid the death bed at the end.

In other words, we wait.

chuck doesn’t like waiting rooms

Sadly, the thing about waiting rooms is that they’re designed to keep you comfortable enough that you forget you’re supposed to leave. There’s bad coffee. There’s Wi-Fi. There’s 3-year old gossip magazines. There’s always one more article about “10 Ways to Finally Become Your Best Self.” You can spend your entire life in there, convincing yourself that preparation is the same thing as living.

And December has become the most insidious waiting room of all. We’ve culturally agreed it doesn’t count. It’s “the holidays”—a suspended state where normal rules don’t apply. You’re supposed to overindulge, overspend, avoid the gym, eat your feelings, put off difficult conversations. Real life? I haven’t heard of her. That starts January 1st. That’s when you’ll finally become the person you’ve been meaning to be. Better, more organized, actually calling your grandmother instead of just thinking about calling your grandmother. December is just the previews before the film starts.

Except here’s what I need you to take in: Between your ears right now is an entire universe. Every person you’ve ever loved. Every song that’s made you cry in your car. Every late night conversation where you finally felt seen. That moment you laughed so hard you couldn’t breathe. Your mother’s hands. The way certain streets smell in summer. Every book that changed you. Every meal that mattered. All of it—decades of moments and memories and people and places—lives inside you. You’re not a rough draft. You’re not under construction. You’re a walking universe that’s been thirty, forty, fifty years in the making.

And you’re treating December like it doesn’t count.

I have a Google Doc called “2026 Ideas” that I started in October. Twenty-five bullet points. “Finally learn to poach an egg properly.” “Be the kind of person who goes to farmers markets.” “Call my family more often”. Things I could do literally right now, today, this afternoon. Things that require nothing except deciding they matter. What have I done from that list?

Nothing.

Because the doc isn’t called “December 2025 Ideas”—it’s labeled 2026, which means I’ve given myself a free pass to not start yet. My mum keeps asking if I’m coming home for a few extra days before Christmas. I keep saying “I’ll see, I’m really busy” when the truth is I’m not busy. I’m waiting for the price to miraculously drop. Waiting for January when I’ll supposedly transform into someone who deserves five days off to sit in her childhood home eating melomakarona while her mum fusses about whether she’s wearing enough layers. I have a blazer in my closet that cost £300. I bought it in 2022. The tags are still on. I’m saving it for a special occasion that apparently hasn’t arrived yet in three years. I’ve also been saying I want to write a screenplay for two years now. I have the concept, I have pages of notes, I have some scenes. But I keep telling myself “once 'I’ve taken a proper course"” or “once I figure out my voice better.” Darling, the timing will never be perfect.

This is Albie logic. Chuck stood in that cupola, saw his death at 39, and told himself: I am wonderful. I deserve to be wonderful. And I contain multitudes.

Not “I will be wonderful once I fix myself.”

Not “I’ll deserve it after I’ve completed my to-do list.”

Nobody gave him that permission. He had to tell himself. But luckily, my reader, you have me. So I’ll tell you.

You are wonderful. Right now. The you reading this, probably procrastinating, probably with seventeen browser tabs open and a half-drunk cup of something gone cold. The you who hasn’t checked everything off the list. The you who’s been sitting in December’s waiting room thinking January is when your real life starts. You contain multitudes. Which means you’re already wonderful. Which means you already deserve to be wonderful.

Here’s what I want you to do, and what I’m absolutely going to fail at doing myself but am going to try anyway: Find your street drummer. What’s the thing you’ve been telling yourself you’ll do later, when you’re ready, when you deserve it, when conditions are perfect? The person you’ve been meaning to call for six months. The book you’ve been researching but not writing. The trip you’re saving for “someday.” The album you’ll make when you have more time. (Girl. You don’t get more time. You get the time you have, and then you get dust.) The apology you owe someone. The hobby that feels too frivolous to start. The doctor appointment you keep almost booking. The expensive wine you never order because you always pick the second-cheapest. The tattoo. The phone call home to say yes, actually, I’m coming early and staying late and we’re watching Love Actually dubbed in Greek even though we’ve both seen it 800 times.

Whatever your version is, and you know what it is, you’re thinking about it right now, hear this: You don’t have to earn it. You’ve always deserved it. The world was made for this moment. Not January 1st when you’ve finally fixed yourself. Right now. Today. This exact minute. You’re wonderful. Act like it.

🫦 A final note 🫦

P.S. Apparently hitting that little heart button is the equivalent of leaving a good tip for the algorithm™ gods. So if you enjoyed this essay, please give it a like. And if you’re sharing any of these takes in the wild (bless you), tag me - I love seeing which parts made you go “YES FINALLY SOMEONE SAID IT.” Sharing is also deeply appreciated because, you know, sharing is caring and all that cinema-loving jazz.

I saw this by myself in an empty theatre and bawled at the dance scene. Big supporter of living for the now.

Delightful. I saw this in theaters, and was initially worried after reading reviews complaining about how it was too "saccharine sweet".

Like Shawshank or one of King's other non-horror stories, I was captivated and found it enjoyable, and thought provoking.

I stumbled across a term a few months back that made me pause: "Insecure overachiever." I realized it was how I lived a good portion of my life: driven to succeed so that I could one day feel like I could be "enough." Waking up each morning feeling behind before the day had even started.

(Of course, "enough" was always juuuuuust out of grasp, combined with impostor syndrome, etc.").

It's been pretty freeing when I've changed this mindset to accepting I'm where I am right now, doing what I'm meant to be doing.

Thanks for writing a wonderful essay. We need more Chucks, a few less Albies.