did i just invent the formula for underrated directors?

A term that reveals more about us than the directors we apply it to.

I was scrolling through Letterboxd the other day, when a review popped up calling All That Jazz "criminally underrated" and I nearly threw my phone across the room. A film preserved in the National Film Registry, winner of the Palme d'Or, with four Oscars and universal critical acclaim? Underrated?

This encounter sent me tumbling into a weeks-long investigation of the term "underrated" as both linguistic construct and cultural phenomenon. Film criticism scholars have identified that it ostensibly refers to something valued below its true worth, but immediately creates a paradox: underrated by whom? Against what standard? According to what criteria?

Browsing through subreddits, I found the term operating less as critical assessment and more as social currency. Someone called Aki Kaurismäki "underrated" because he doesn’t “see many people talk about his films even though he's released quite a lot of them." Pedro Almodóvar was characterized as underrated from someone else because they “have a lot of friends who are film fans who haven't watched a single film in his filmography." Similarly, directors like Jafar Panahi, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, and Theo Angelopoulos are listed as "underrated" despite their significant critical acclaim in art house and international cinema circles.

Unsurprisingly, this label disproportionately attaches to certain filmmakers while it bypasses others. Brian De Palma has been touted as "underrated" for decades, despite his films getting Criterion releases while simultaneously being dismissed as Hitchcock knock-offs. His reputation exists in superposition, both canonized and overlooked, depending on who you ask. Meanwhile, filmmakers like Euzhan Palcy and Julie Dash created foundational works only to face industry-wide silence.

The designation of the word becomes further complicated when we examine how directors' reputations fluctuate over time. John G. Avildsen, despite winning an Academy Award for Best Director with "Rocky," has become "essentially a forgotten name." Martin Brest gifted us Midnight Run and Beverly Hills Cop before Gigli effectively exiled him from cinema. Does his vanishing from the directorial landscape constitute being "underrated”?

Yet, there's something about the word that keeps us coming back. Because sometimes, against all odds, someone makes something genuinely excellent that doesn't get its flowers. And we don’t have the perfect argument for why that is. It happens! The algorithms fail, the marketing fizzles, the zeitgeist zags when it should've zigged.

So when I asked my asked my Threads followers to name directors they feel are not celebrated enough, I wasn't surprised when hundreds replied with filmmakers spanning every continent, era, and budget tier. Some names didn't surprise me (Terrence Malick, who’s got 3 Oscar nominations but somehow still gets brought up a lot???). Others were so obscure I'm convinced several of you made them up (nice try with Khyentse Norbu – I googled and he's real, I’m checking out their work as we speak).

This all left me wondering: could we actually measure "underratedness" with any objectivity? Or is it forever doomed to be the "vibes-based metric" of film criticism?

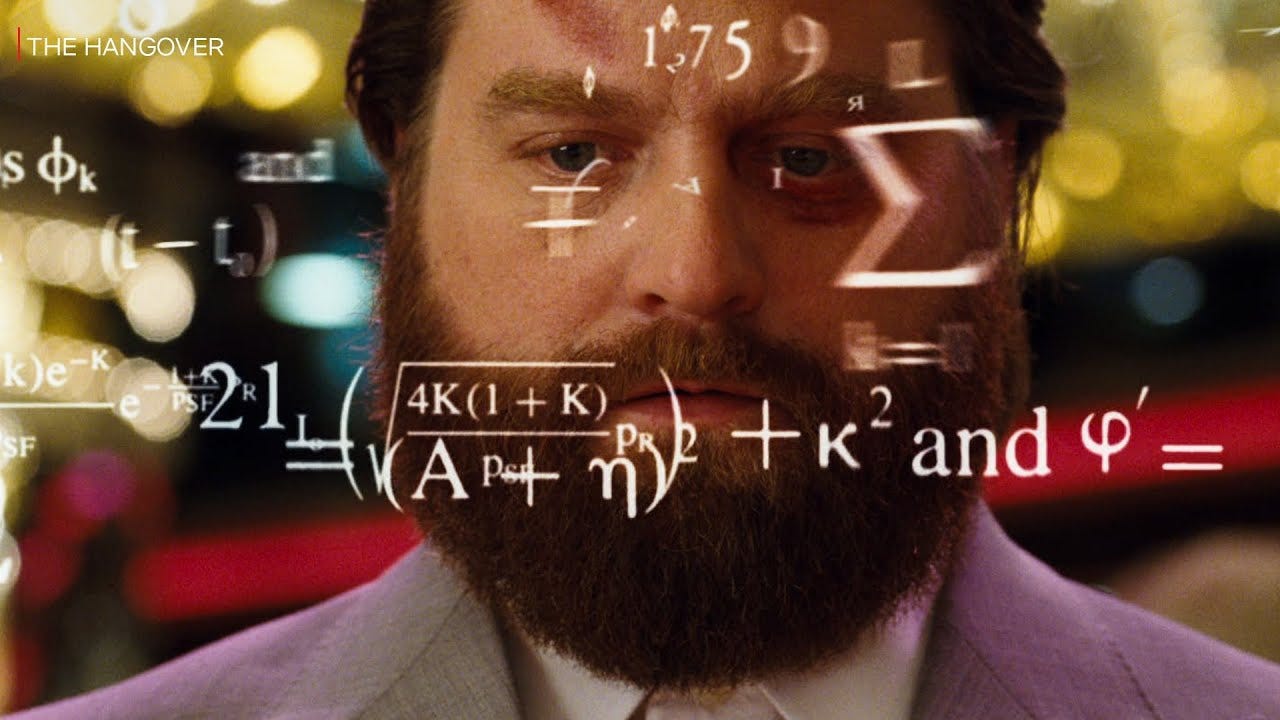

So I did what any normal person would do: I attempted to create a formula.

A scientific attempt to measure underratedness that is not to be taken seriously

First, let's break down the fundamental equation. To be underrated requires two things:

Quality (how good someone actually is)

Recognition (how much attention they receive)

Conceptually, it's simple:

Underratedness = Quality ÷ Recognition

If quality is high but recognition is low, the ratio gets bigger, suggesting "underrated."

But this simplistic approach immediately falls apart. For starters, how do we quantify "quality"? And how do we account for the fact that filmmakers work in wildly different contexts? A director making experimental films in Thailand faces a completely different recognition landscape than someone churning out midbudget dramas in Hollywood.

So I built a more nuanced approach.

Step 1: Creating a Quality Composite

I imagined a proper Quality Composite that blends:

QualityComposite = wcrit × Critics_Score + waud × Audience_Score + wawrd × Awards_Index

Where:

wcrit, waud, and wawrd are weights (because I still believe poor critic reviews can bury films - see Emilia Pérez)

Critics_Score is the average Metacritic/RT percentage across all films

Audience_Score is the average IMDb/Letterboxd rating (normalized to a 0-100 scale)

Awards_Index is a weighted sum where each Oscar = 10 points, each nomination = 5 points, etc.

But this isn't granular enough. Most "underrated" directors haven't won Oscars, so we need to include festival awards and regional honors:

Awards_Index = ∑(Points for each win/nomination)

A proper table would have dozens of entries like:

Oscar (Best Director/Picture): 10 points win, 5 points nomination

Cannes Palm d'Or: 9 points win, 4 points nomination

César (France): 6 points win, 3 points nomination

Blue Dragon (South Korea): 5 points win, 2 points nomination

…and so on.

Step 2: Creating a Recognition Composite

Next, I'd need a Recognition Composite that accounts for just how invisible some truly great directors remain:

VisibilityComposite = wvis × Visibility_Index + wpress × Press_Index + wbox × BoxOffice_Index

Where:

Visibility_Index combines search volume and social media presence

Press_Index measures mainstream media mentions

BoxOffice_Index calculates total box office adjusted for inflation, budget, and release context

Step 3: Normalizing…as much as I can

This is where things get tricky. I realized any formula would need to normalize everything based on a director's primary context. So we’d somehow need to also account for:

Time periods: Michael Powell has zero TikTok followers because he died in 1990, not because he was unpopular

Different film industries: A Bollywood director might have 600 million domestic viewers but remains unknown in the West

Budget contexts: An experimental filmmaker will never match Marvel’s box office

So I'd need to normalize by era, region, AND style:

Critics_Score_Normalized = (Director's Critics Score - Mean Score of Directors from Same Era/Region) ÷ (StdDev of Directors from Same Era/Region)

Audience_Score_Normalized = (Director's Audience Score - Mean Score of Directors from Same Era/Region) ÷ (StdDev of Directors from Same Era/Region)

Awards_Index_Normalized = (Director's Awards Index - Mean Index of Directors from Same Era/Region) ÷ (StdDev of Directors from Same Era/Region)

Then I'd build a normalized Quality Composite:

QualityComposite_norm = wcrit × Critics_Score_Normalized + waud × Audience_Score_Normalized + wawrd × Awards_Index_Normalized

And do the exact same thing with all the Visibility components:

VisibilityComposite_norm = wvis × Visibility_Index_Normalized + wpress × Press_Index_Normalized + wbox × BoxOffice_Index_Normalized

Watch actual mathematicians come at me in 3, 2, 1….😭

Step 4: Introducing the final formula

With normalized components in hand, we could build the master equation:

Underrated_Score = QualityComposite_norm ÷ ln(VisibilityComposite_norm + 1)

Why the logarithm? Because1 popularity measures can span ridiculous ranges. Spielberg might get millions of Google searches while an obscure documentarian gets dozens. A logarithmic scale compresses these differences.

Step 5: Addressing the harsh reality

Staring at this equation while my neighbors blast what sounds like a Skrillex funeral dirge made me realize that this entire methodology is, in fact, fundamentally absurd.

Even with perfect normalization across every possible variable, I’m still trying to quantify something inherently subjective and emotional. Therefore, underratedness is not just mathematically difficult to define, it's ontologically impossible.

And I believe this is because it operates across three dimensions that refuse to be defined:

1: Quality is a mirage

We talk about film quality like it's observable fact, but it's all built on shifting sand. What my formula couldn't account for is that "good" itself is contested territory. When I call someone underrated, I'm really placing a bet against consensus, saying "future generations will prove me right." But how many "once-in-a-generation geniuses" have disappeared completely? How many "underrated masters" will never get their retrospective at Film Forum? The quality variable in my equation pretends to measure something concrete, but it's really measuring belief: My belief that I know better than everyone else.

2: Underrated by whom?

Recognition doesn't travel evenly. Kelly Reichardt is simultaneously "the most important American filmmaker working today" and "who?" depending entirely on who you ask. My formula tried valiantly to normalize for audience, but there's no calculus complex enough to capture how reputation fractures across different viewing publics. The recognition variable isn't measuring a static value but the distance between two worlds: the world where this filmmaker is appreciated exactly as we believe they should be, and the reality we perceive.

3: Reputations mutate in public memory

Remember when Kathryn Bigelow was that "director who made Point Break" before she became "first woman to win Best Director" before she became "problematic"? Reputations are unstable objects moving through time. Today's "overlooked genius" is tomorrow's "overexposed hack" is next week's "rediscovered visionary." My poor formula crumbles against this. Stamp a value on a director today, and time will make you look like a fool tomorrow.

What’s become clear to me from this little quest is the following: When we call a director "underrated," we're not making a claim about the director at all. We're revealing our relationship to consensus. We're saying: "I reject the going rate. I'm pricing this differently." It's an emotional position disguised as critical assessment.

No formula can capture that. But perhaps that's the point—the subjectivity is the message. The very impossibility of my equation might be the most honest answer to what "underrated" actually means.

moving beyond the “underrated” label

Among the directors people on Threads insisted deserved more recognition: Martin Scorsese, George Clooney, John Ford, Paul Verhoeven, Emerald Fennell, and Clint Eastwood. Scorsese, a man whose eyebrows have received more scholarly analysis than most directors' entire careers. Fennell—a director with two feature films, one of which I never want to hear about again (please read Inigo Laguda’s review of Saltburn immediately). Clooney…literally no idea why his directing needs to be celebrated any second longer.

The aforementioned are clearly not overlooked auteurs. They are the definition of the established canon. Yet here are film lovers positioning them as somehow neglected.

I get the urge to use the word. Truly! Calling something "underrated" scratches a particular cultural itch—it positions us simultaneously as connoisseurs who recognize quality and as champions fighting against an unjust status quo. It offers the emotional satisfaction of discovery without requiring us to look beyond established canons. We get to feel both culturally secure (these directors are validated enough to know) and culturally superior (we appreciate them more than others do).

Our streaming landscape only intensifies this. Algorithms don't register vague claims about being "criminally overlooked." They track specific engagement. Netflix won't suddenly promote Janicza Bravo because Letterboxd thinks she deserves more followers, but it might respond to viewers engaging deeply with her visual language. The granular, specific appreciation that might actually redirect cultural attention is precisely what our lazy "underrated" shorthand evacuates.

Our cultural championing languishes when trapped in reflexive labeling toward something that transforms awareness into engagement. The directors who we often call overlooked don't suffer from some abstract "underratedness"—they face concrete barriers that require concrete language to dismantle. Agnes Varda's career didn't achieve the same institutional recognition as her French New Wave contemporaries not due to 'quality' but because, as she noted, with each new film she had to 'fight like a tiger'. Franco Piavoli's visual symphonies don't struggle from lack of artistic merit but from distribution systems that relegate non-narrative cinema to festival circuits and university screenings, regardless of their transformative power. These specific problems demand specific vocabulary.

The path forward isn't a better rating system2 but abandoning the competitive framework that "rating" itself imposes on art. What if we developed a critical vocabulary built not on comparative judgment but on specific resonance? What if, instead of constantly situating directors on some imagined continuum of recognition, we simply articulated what makes their work essential?

Cinema deserves this more exact language not because I'm a linguistic purist but because precision creates pathways for genuine discovery. The next time you feel that reflexive "underrated" impulse, push yourself one step further. Ask what specific quality you're responding to, what unique perspective you've recognized, what particular innovation has moved you. Tell me why these filmmakers matter, not just that they should.

I began this investigation irritated by hyperbole. I end it questioning our entire framework for advocating art we love. Let’s create change in what’s happening in conversations between viewers, in specific moments of recognition, in how we talk about films as unique experiences rather than items to collect or positions to hold.

Ultimately, being crowned 'criminally underrated' carries zero industry capital. Filmmakers build legacies when audiences engage with their work and when the industry invests in vision rather than waiting for the retrospectives to kick in.

Made-it-to-the-end bonus 💌: Here are 6 directors from the Threads nominations who I think demonstrate the contradictions mentioned earlier:

directors critically celebrated, institutionally ignored

Lynne Ramsey

Ramsay films violence like nobody else – not the act itself but the void around it. We Need to Talk About Kevin skips the school shooting entirely to excavate the psychological wreckage before and after. You Were Never Really Here turns Joaquin Phoenix into a hammer-wielding avenger but keeps his brutality mostly offscreen, focusing instead on the brief moments he sings with his dying mother. The industry keeps Ramsay on a starvation diet – four films since 1999, with more collapsed projects than completed ones. Her adaptation of The Lovely Bones disintegrated when studios demanded heavenly voiceovers to comfort audiences. Her Western with Natalie Portman imploded days before shooting. The suits beg for her visual instincts then balk at her refusal to soften her perspective.

Charles Burnett

Killer of Sheep now sits in the Library of Congress, but it took thirty years of critical championing to pull it from obscurity. Burnett shot it for $10,000 as his UCLA thesis film, using friends as actors and capturing 1970s Watts with a documentary-like immediacy that makes most other American films of the period feel stage-managed. While Scorsese became synonymous with American cinema, Burnett's career took detours through PBS and even Disney Channel.

To Sleep With Anger might be his masterwork. Danny Glover's Southern trickster figure upends a Black middle-class LA family through folk beliefs that oscillate between comedy and supernatural threat. The Academy finally gave Burnett an honorary Oscar in 2018, but this kind of retrospective validation only highlights the decades of opportunities he should have had. His work exists in a state of perpetual critical rediscovery without ever quite achieving the cultural centrality it deserves, perfectly illustrating how "value" in cinema can be recognized on paper without translating to actual industry power.

directors adored in one universe, invisible in another

Hlynur Pálmason

Iceland produces filmmakers the way it produces volcanic eruptions: infrequently, but with devastating impact. I discovered Pálmason's A White, White Day a few years ago, and found myself transfixed by his visual grammar. The film uses Iceland's notorious fog as both setting and metaphor for a grieving man's clouded judgment. His follow-up Godland sent a Danish priest on a soul-crushing journey through 19th century Iceland that turned landscape photography into psychological warfare. I've never seen terrain captured with such visceral animosity.

Yet mention Pálmason's name at any multiplex in America and you'll get blank stares. His critical acclaim remains quarantined within festival circuits and arthouse theaters, his films rarely breaking beyond the self-selecting audience who actively seek out Icelandic cinema. His work exists in two parallel dimensions: one where he's hailed as a visionary image-maker redefining the relationship between character and environment, and another where he might as well be directing underwater puppet shows for all the cultural impact he has.

Mika Ninagawa

When male directors create hypervisual fantasias, they're visionaries. When Ninagawa does it, critics dismiss her as style over substance. Her background in photography translates to frames so saturated with color they practically drip off the screen, but to Ninagawa, these are her secret weapons. Helter Skelter turns the fashion industry into a horror show of feminine self-destruction, while Diner serves up poisoned meals as metaphors for consuming patriarchy. Her visual excess makes perfect sense when you realize she's depicting worlds where women are force-fed impossible beauty standards until they rupture. Nonetheless, her audience split is stark: revered in Japan, especially by women viewers, while Western critics can't get past their gendered double standards.

directors overtaken by the harshness of time

Edward Yang

I once skipped a friend's birthday party to rewatch Yi Yi alone in my apartment. We don't speak anymore. Zero regrets. Yang made films with the patience of a sniper – his camera observes Taiwanese city life with such stillness you forget someone's directing at all. A businessman comes home, loosens his tie, stares out the window. Nothing happens. Everything happens.

A Brighter Summer Day spans four hours of teenage alienation in 1960s Taiwan, building such slow-burning tension that when violence finally erupts, it ambushes you. His actors don't seem to perform so much as exist – a trick so difficult it looks simple to anyone who hasn't tried filmmaking. Yang died at 59 with just seven features to his name. This math feels criminal when Adam Sandler got to make Grown Ups 2.

Elaine May

I watched The Heartbreak Kid during a pandemic spiral and laughed so hard my neighbor banged on the wall. May only made four films before Hollywood dumped her, the surest sign of her brilliance. No industry kicks out mediocre talents; they promote them to executive producer. Her camera turns on male insecurity with such precision in Mikey and Nicky that you smell the cigarettes and flop sweat. Two "best friends" in a hotel room – one planning the other's murder. Pure American pathology. Then Ishtar happened – the "bomb" that ended her career. I rewatched it last month. It's a slapstick satire about clueless Americans fumbling through Middle Eastern politics while thinking they're heroes. The film didn't fail. We failed it.

A final note for people with taste 🫦

While the internet's prioritizing hot takes and SEO-optimized nothingness, I’m here trying to build a sanctuary for people who believe film and television criticism can be thoughtful, accessible and fun all at once.

For the price of a truly mediocre sandwich, join the resistance with a paid subscription – it keeps independent film writing alive and the algorithms at bay.

Plus, you'll get exclusive access to After Credits, my monthly handpicked watchlist of films & tv shows that will stop you from doomscrolling AND access to my more personal takes and essays.

Now go forth and raise those standards, darling.

- Sophie x

According to Google, don’t @ me. The last time I thought of logarithms was in high school.

Speaking of rating systems, I wrote an essay on this callled ‘who decides the greatest film ever made?’.

This is a great piece! I do think the term underrated gets thrown around so much just because a lot of people (including myself) will just really vibe with a work of art and not have the words to describe why. Art is subjective, so it's really hard to explain why something had such an impact on you.

I also love Mikey and Nicky. It is my favorite film that I will never watch again because of how sad it is. Also the funniest depressing movie I have ever seen.

Excellent stuff, and utterly mindboggling. I've been sitting here trying to define it myself and failing miserably: the closest I can come is if a director has had a book-length study or documentary about their work, then they're probably not underrated in any meaningful way. That might throw out Elaine May, though, and I don't want to throw out Elaine May because she's one of the all-timers.

Just because he's been on my mind (and on my telly) of late, I'd probably say Michael Ritchie, who tends to get lost in the '70s New Hollywood celebrations a bit, wasn't particularly lauded at the time, and who definitely had a thematic through-line. But I don't know. My head hurts. I'm gonna have a wee lie down.