fyi, i'm joining the coven (that is Substack)

Oooo boy. That Final Scene is now on Substack. My lovelies, I've arrived.

So…I disappeared. I know, I know. If you’ve been following The Final Scene on Instagram, you’ve probably been wondering where the hell I went. One minute I’m posting about film endings (Sound of Metal<3), and the next I pull a Keyser Söze.

It’s not that I didn’t want to keep posting—it’s that Instagram became exhausting. And by “exhausting,” I mean the kind of soul-sucking where your feed just screams "do more Reels! post more Stories! leave 100 comments a day! you forgot that 29th hashtag!" and suddenly you're expected to be a video editor and a writer and a content creator and probably a magician.

So here's the truth: I broke. Cracked under the weight of endless posts, reels, and that goddamn algorithm. Every day, another platform update, another trend, another desperate attempt to stay relevant. To stay seen.

And for what? A dopamine hit from likes? The fleeting validation of virality?

Fuck that noise.

6 years ago, I didn't start my page to become a human content machine. I started it because I love stories. Because I believe that how a story ends says something profound about who we are, what we value, what we fear.

And y’all know that while I still love my podcast with Ben and Simon (shoutout to my co-host bbs), writing has always been the love of my life.

Which is why I’m here. On Substack. Not entirely sure what form this newsletter will take yet, but hey, it’s going to mostly be about what I’ve always loved: stories on screen. Sure, I’ll occasionally break down film endings, but also I want to explore how our (least) favourite stories reflect the state of the world. Other times, maybe I’ll talk about how they mirror personal dilemmas (Why do dystopian films always hit harder during election season?). Or maybe I’ll take you on a journey through horror endings across eras1. I’m still figuring it out—call it my developmental arc.

To those who've stuck around through my radio silence — thank you. Your support means more than you know. And to those just joining us — welcome to the party. I hope you're ready for some spirited debates and probably too many em dashes.

I've missed this and I’ve missed you more than words can say. So let's skip the small talk and dive right in, shall we? We've got a lot of catching up to do.

So…covens.

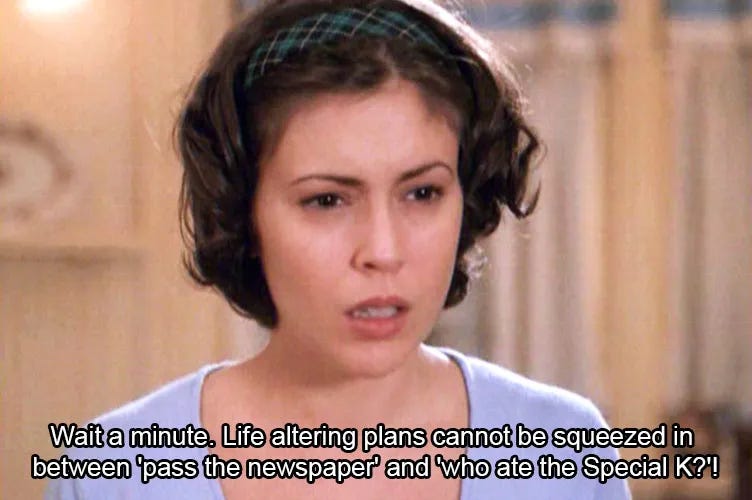

I’ve always had a thing for witches. Maybe it’s because I grew up watching Charmed, convinced my sisters and I were some kind of low-budget Halliwell clan. As the youngest, I was clearly Phoebe—impulsive, psychic (in my mind), and always on a quest for something bigger. My sisters, much older than me, had full-on Prue and Piper energy—protective, powerful, the ones with the serious power. We still have a group chat called “Charmed,” and it’s full of spells we joke about casting on annoying coworkers and Mercury retrograde complaints (jk..maybe).

But for all the power in those Halliwell sisters, their magic always felt safe. It came with rules and limits. The witches of the 90s and early 2000s fought evil but kept everything balanced, always veering toward the moral high ground as though they were auditioning for the Good Place.

Rewind to the '40s, and witches weren't all that different. Take Veronica Lake in I Married a Witch (1942)—her power, while real, circled back to love and marriage, neatly tied to societal norms like a 1950s housewife's apron. Magic had its place, and it wasn't in rebellion. It was still tamed by romance or some social purpose, like a declawed cat allowed to roam the living room.

Then Agatha Harkness sashayed into WandaVision, and suddenly we're not in Kansas anymore, Toto. From the jump, she was difficult. She wasn't easy to like—too pushy, too intrusive, too willing to step over boundaries like they were chalk lines on a playground. I found it unsettling. Agnes, the quirky neighbour routine, felt off. I didn't realize it at the time, but I was waiting for her to fit into the pop culture witch mold I was used to—fun, quirky, maybe a bit edgy, but ultimately "good" like a Glinda the Good Witch after a few shots of tequila.

My discomfort hit DEFCON 1 when the first episode of Agatha All Along dropped. Suddenly, it hit me like a ton of broomsticks. The problem wasn't Agnes. It was me. I'd been waiting for her to become likeable, to justify her ambition, to fit within the rules. But Agatha wasn't concerned with being understandable, let alone likeable. She was the honey badger of the MCU—utterly indifferent to anyone's opinion.

In the '90s, witches balanced their strength with vulnerability. Sabrina needed her aunts to keep her in check, while Buffy had a destiny she couldn't escape — trapped in some cosmic game of tag where she was eternally "it." Even in The Craft (1996), Nancy's ambitions were punished when she overreached, leading to her downfall. It was a pattern—a witch could be powerful, but only if she eventually paid the price, as though power came with some twisted magical credit card.

But Agatha reminds me more of the witches I wasn’t supposed to admire. The witches of Suspiria (1977), whose power pulsated through blood-red rooms without apology, turning the screen into some twisted, neon-soaked rave. The Witches of Eastwick (1987), who took and consumed without concern for the fallout, treating the world as their personal all-you-can-eat buffet of chaos. Women who didn't tether their power to anyone's comfort, who claimed it because it was theirs to claim, as casually as picking up dry cleaning.

Agatha taps into something primal. Channeling Barbara Creed's 'Monstrous-Feminine,' she's a woman who isn't here to be controlled or softened. She's chaos incarnate, and she's not bothering with a pretty bow. She fits that lineage, unbound by the need to be morally digestible. She's not your poster woman for #Witchtok.

The power of these characters ties into Julia Kristeva's theory of the "abject," which explains why figures Agatha unsettle us more thoroughly than a haunted house on steroids. Kristeva describes the abject as that which disturbs identity, order, and system—what exists outside the borders of what is acceptable. Agatha makes no attempt to fit within those borders. She bends the world around her, instead of shaping herself to fit it, turning reality into her personal game of Twister where she's always calling the shots.

It is the very lack of justification that makes Agatha's power so profoundly disruptive. It feels radical because it is radical. I had been waiting for her to explain herself, but the brilliance of Agatha is that she doesn't explain anything. She moves, she shifts, she takes. She's the living embodiment of that Beyoncé lyric: "I'm not sorry, I'm not sorry, I'm not sorry."

This same abjection is present in The Witch (2015), where Thomasin's final walk into the forest speaks to a rejection of societal constraints with the subtlety of a Rage Against the Machine concert (final scene alert!!!!). When she whispers "I will," it feels a reclamation of a power that was always hers but was never allowed to be named. The forests, the covens, the spaces outside of civilisation have always represented freedom for witches. Agatha taps into that same energy—the energy of women who refuse to be contained, whose power has no leash.

The queerness of Agatha's character deepens this narrative of defiance. Witches have always been queered figures, standing at the edge of societal norms with the casual balance of a tightrope walker on a very fabulous wire. From the queerness coded in The Love Witch (2016), to the camp energy of The Witches of Eastwick, witches have long represented "otherness". Agatha's relationship with Rio Vidal (Aubrey Plaza i love you) crackles with that same energy—it's not about tenderness but shared hunger. For power, for chaos, for rejecting any system that would contain them. Their bond is a rewriting of what power and intimacy can look like. It reminds me of this poem from Rupi Kaur’s “milk and honey”2:

“i do not want to have you

to fill the empty parts of me

i want to be full on my own

i want to feel so complete

i could light a whole city

and then

i want to have you

cause the two of

us combined

could set

it on fire”

Agatha unsettles me because I had never been taught to admire women who didn't apologise for their power. Characters like Wanda, whose strength is always wrapped in grief and guilt, follow the scripts that make female power palatable. Wanda's trauma makes her magic something we can understand, something we can sympathise with. Agatha offers no such sympathy. Her ambition isn't softened by suffering. She wants power because she wants it, and that alone shakes everything I had come to expect from women on screen. It's not that she enjoys chaos—it's that she doesn't see chaos as something to fear. She's not leaning in. She's kicking the door down with the force of a battering ram.

We've been conditioned for so long to see female ambition as something that must come with suffering, or at the very least, redemption. But Agatha doesn't care about being redeemed. We're not used to watching women embrace power without some form of struggle, apology, or moral justification. And Agatha is that freedom3.

It took time for me to understand why I initially had such a visceral reaction to her. The discomfort wasn't about her character, per se, it was about how deeply I had internalised the idea that powerful women (witches?) should struggle, that they should explain themselves, that they should soften their edges. It was realising that unwillingly, I'd been wearing glasses with the wrong prescription, and Agatha had just handed me the right pair.

Agatha embodies what witches have always represented at their core: a rejection of any system that dares to control them. She’s a witch for a world that’s tired of asking for permission. And honestly? That's the kind of energy I want to channel in 2025. Less "So sorry for the delayed response" and more "You're welcome for my response."

Who's ready to join this coven?

That's a wild overpromise. I still haven't recovered from my Titane squishiness so do not expect a Substance review from me anytime soon.

If Rupi Kaur's "milk and honey" isn't on your bookshelf yet, you're missing out on poetry that packs more punch than a triple espresso and hits harder than the realization that you've been mispronouncing 'quinoa' for years. It's the literary equivalent of a witchy brew - potent, transformative, and likely to leave you slightly dizzy but totally spellbound.

I say this as if it's a punishment, but let's be real, I'd probably enjoy every minute of it. Don't judge me.