my essential films of 2020-2025 (part 2)

More films from the 2020s I can't stop thinking about.

ICYMI: I posted Part 1 a couple of weeks ago ✨

A few hours after I posted Part 1, I got a text from a friend asking if I’d deliberately picked films that had people treating each other like glass. I hadn’t noticed this until she said it, but she was right—even when characters were falling apart or getting divorced, they moved through scenes like they were afraid of shattering whatever fragile thing was holding them together.

When I started drafting the 2023-2025 list, I realized none of the films I wanted to include had that quality anymore. I watched the Hollywood strikes happen in summer 2023, scrolling through Instagram stories of writers holding signs outside studio gates while streamers were simultaneously deleting shows from their platforms for tax breaks (throwback to Westworld vanishing overnight). I remember friends working in the industry telling me that their projects that had been greenlit were gone for “restructuring”. Then the actors joined and everything stopped for months.

At the time, my naive brain was telling me it was all temporary, surely production would resume and things would stabilize. On the contrary, we witnessed Max rebrand from HBO Max because apparently three letters was too much prestige to maintain. Netflix announced they were going “all in” on AI content production. Clearly, the industry would rather invent technology to replace you than pay you what you’re worth.

The films I picked for Part 2 came out during or after that collapse, and they carry that exhaustion with them—not despair exactly, but a total absence of pretense that things were going to get better.

So let’s get to them.

2023

tár (Todd Field)

Todd Field put Cate Blanchett in a men’s suit and let her conduct an orchestra like she was performing open-heart surgery, and somehow that became the least interesting thing about Tár. I’m talking about a film where a woman has clawed her way to the top of classical music—a field that treats women like decorative plants—and now she’s the one doing the destroying. She grooms her students. She tanks careers over perceived slights. She records herself sleeping to catch evidence of her own nightmares. Field shoots all of this with zero commentary, like he’s David Attenborough observing a apex predator. You’re simply watching someone unravel because the machinery of power always, always eats its operators.

The 2020s gave us a thousand conversations about accountability and none of them prepared us for a film that shows what happens when the reckoning arrives not as justice but as irrelevance. Power protects itself until protection becomes expensive, then it finds a new host. Blanchett plays this with her entire body, all angles and contained violence, and by the end she’s conducting in Manila for gamers who don’t know her name. The film doesn’t ask you to feel bad for her. It asks you to recognize that the machinery doesn’t care who’s operating it.

anatomy of a fall (Justine Triet)

I spent the entire runtime of Anatomy of a Fall white-knuckling my armrest because Justine Triet refuses to let me off the hook, and I mean that as the highest compliment I can give a filmmaker these days. We’re living through the great flattening—cultural moments instantly processed into good guy/bad guy choices, ambiguities steamrolled into certainty by people who’ve decided that holding two contradicting thoughts is a moral failing. Then here comes Triet with Sandra Hüller’s writer on trial for maybe-murdering her husband, and the film sits you in a room with a marriage so knotted and frayed that truth becomes beside the point. I love this film viciously because it uses memory as slippery, self-serving, and revised in real-time depending on who’s asking the questions.

The courtroom is a theater where everyone performs their version of events, and Triet films it with such forensic attention that you start noticing how testimony is just storytelling with higher stakes. Every time I thought I’d landed on a verdict, the film would unspool another conversation, another recording, another moment that scrambled my certainty back to static. Hüller’s face does tremendous work here—she’s not playing innocent or guilty, she’s playing someone exhausted by the demand to be legible, to fit neatly into the story the prosecution needs. 2023 was the year we probably lost all our ability to sit with uncertainty, yet Anatomy of a Fall managed to build a cathedral to ambiguity. It trusts you to live inside discomfort, to recognize that people contain multitudes and marriages are ecosystems we can never fully parse from the outside. Watch this if you miss cinema that respects your intelligence, that doesn’t hand you answers because life doesn’t work that way.

past lives (Celine Song)

I left Athens for London ten years ago and the trade-off seemed straightforward: shed the accent, learn to small-talk about the weather, stop gesticulating like I’m conducting an orchestra, become the kind of woman who may one day get cast in British productions instead of playing “ethnic friend” forever. Past Lives obliterated me because Celine Song filmed the exact texture of that bargain—not the romantic version where you stay connected to your roots while thriving abroad, but the one where you amputate your past self and spend precious time pretending the phantom limb doesn’t ache.

Greta Lee sits in New York bars speaking Korean to her childhood love while her American husband waits nearby, and I recognized that special hell of being fluent in a language you’ve deliberately let corrode. My family speaks to me in this careful, translated Greek, and I do the same terrible math Lee’s character is doing: how much did I lose? Can you measure it? Would I trade it back if I could? Song shows us that assimilation isn’t code-switching between two intact identities. It’s amputation. You cut off the version of yourself that can’t survive in the new country and then keep insisting you don’t miss it. The film sits you down and makes you witness someone realize they can’t undo the choice even if they wanted to. Lee’s character chose America, which meant choosing English over Korean, a white husband over her first love, a career that required erasing the girl from Seoul who would have made different choices entirely.

I’m including this film in this list because we’re drowning in immigrant narratives about finding yourself, honoring your culture, staying connected. But Song’s film is about winning by the rules America set and discovering the prize is loneliness in three languages.

saint omer (Alice Diop)

Alice Diop shoots courtrooms the way Chantal Akerman shot kitchens. Static camera, durational time, zero relief. Saint Omer is two hours of watching a trial where the verdict matters less than watching two women realize they’re trapped in the same impossible performance. There’s a novelist in the gallery, Senegalese, pregnant, supposedly researching a book. There’s a woman on trial, also Senegalese, accused of something unforgivable. Diop keeps cutting between them until you can’t tell who’s really being examined. Both learned French perfectly. Both absorbed the right cultural codes.

The difference between them is just circumstance and luck, and the film won’t let you look away from that. Diop came from documentary and she brings that rigor. Testimony unfolds in real time, lawyers repeat themselves, the bureaucratic apparatus grinds on. The woman on trial quotes Wittgenstein and references Duras and the prosecutor loses his mind trying to make her fit into any recognizable story about bad mothers. She won’t cooperate. The novelist sits there taking notes and you can see her entire sense of self collapsing behind her eyes. This is an essential film about how much we demand mothers explain themselves in language that was never designed to hold them in the first place, and how France built an entire legal system around that impossibility.

do not expect too much from the end of the world (Radu Jude)

Okay so there’s this sixteen-hour driving sequence where Angela recruits workplace injury victims for corporate safety videos—think if Errol Morris directed HR training—and between shoots she films these deeply unhinged Andrew Tate TikToks. Like, prosthetic bald head, incel manifestos, genuinely disturbing shit. And I get it. When you’re three energy drinks deep into a gig that pays maybe enough for rent, ironic misogyny starts looking like the only honest performance left. Jude splices this with footage from an ‘81 Romanian road movie where a taxi driver has thoughts, takes breaks, exists as something other than extractable content. The juxtaposition is vicious. That driver had interiority. Angela has metrics. She’s atomized herself across dashcams and TikTok and corporate Zoom calls until there’s no self left to surveil—just fragments that algorithms can parse and platforms can monetize.

This is the 2020s distilled: your degradation is your brand now, your exhaustion is your selling point, and the only rebellion available is performing your compliance with enough irony that maybe it counts as art. Sadly, it doesn’t. The title is diagnosis. Lower your expectations to match your conditions. Angela already has, and she’s filming the whole thing because at least documentation feels like labor she controls. It isn’t, obviously. But let her have this.

2024

sing sing (Greg Kwedar)

The essential cinema of this specific cultural moment (a period I’ve unofficially titled ‘the Great vapidity’) must possess two qualities: irreverence and absolute specificity. Which brings us, with a perfectly arched eyebrow, to Sing Sing. It’s the film that shattered the glass case of polite, procedural prison dramas, replacing them with a glorious, documentary-adjacent din. You see, this film, built on the authentic, lived-in tremors of its incarcerated cast, is a slap in the face to the tyranny of the well-made script. Its energy is less ‘story arc’ and more ‘shrapnel.’ Its presence on my personal required viewing list is a sneering declaration that the greatest acting of the decade isn’t happening in the soundstages of Burbank, but in the volatile chemistry between men who have nothing left to lose but their own self-respect. It’s a film that asks “What do you do when your life is reduced to four walls?” The answer, delightfully, is that you stage a ludicrous play, and in doing so, you save yourself.

challengers (Luca Guadagnino)

Challengers got released at a time when we needed to remember that movies could be horny without apologizing for it, that competition is foreplay, and that sweat can be a protagonist. Zendaya plays Tashi Duncan like a conductor orchestrating a decade-long mindfuck between two men who are either in love with her or each other (correct answer: both), and the film never once pretends this is complicated. It’s simple. They all want to devour each other. The camera knows it. The score—Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross turning tennis grunts into industrial music—knows it. Josh O’Connor eating a churro like he’s trying to make it come knows it. And somehow, that’s less horny than the actual tennis scenes, which Guadagnino shoots like they’re the final ten minutes of a porno where everyone’s about to collapse from exhaustion and satisfaction.

If 2024 cinema needed anything, it needed permission to be unserious about serious things. Challengers walked in, drenched in body fluids and sexual tension, and reminded us that movies can be smart and stupid, gorgeous and grotesque, high art and high camp all at once. It’s less a sports movie than a thesis on why we can’t separate competition from fucking, why winning means nothing if no one’s watching, and why we’ll destroy ourselves for the chance to be seen by someone who sees us completely.

Anyway, I haven’t stopped thinking about its lack of Oscar nominations since it came out and I’m pretty sure that means something. #JusticeForChallengers

nickel boys (RaMell Ross)

I watched RaMell Ross put me inside Elwood’s body for 140 minutes and my brain kept trying to escape into the usual critical distance—like maybe I could think about Bazin or formal innovation or how this compares to other POV experiments—but the fist kept coming at my face, the ground kept rushing up at me, and there’s no retreating into film theory when your nervous system registers that you’re the one being beaten. Ross didn’t make a film about witnessing Black suffering from a comfortable seat. He made something that smashes the comfortable seat entirely.

You cannot look at these boys the way we’ve been trained to look at historical atrocity because you’re not looking at them—you’re looking through their eyes, seeing the white faces of their abusers from the exact angle of their terror, and every formal choice in the film is designed to make that distance we usually maintain while consuming Black trauma completely impossible. Essential feels like too small a word for this film. Nickel Boys is what American cinema looks like when it stops letting us be safely distant witnesses to its own history.

monster (Hirokazu Kore-eda)

The school counselor who pulled me aside in seventh grade to ask if everything was “okay at home” had seen me drawing during math class and decided this indicated trauma. I was doodling because math was boring and I’d finished the worksheet in ten minutes, but she’d already constructed an entire narrative about my home life based on the fact that I’d drawn a girl with no mouth.

Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Monster operates in that exact gap between what adults observe and what’s actually happening, except instead of one misread moment, he stacks three competing narratives on top of each other until you realize certainty itself is the problem. A mother finds bruises. A teacher gets accused. Two boys hide something neither adult could parse even if they knew to look. Kore-eda never tells you which perspective is correct because that’s not how perspective works—everyone’s telling their version of the truth and everyone’s manufacturing their version of the lie, and the violence happens in the space between. This film has a special place in my heart for that reason. You finish it still not knowing who to believe, which is unbearable if you’re someone who needs people to be legible, or needs behavior to be data you can decode.

the beast (Bertrand Bonello)

There’s a scene in The Beast where Léa Seydoux sits in a 2044 therapy chair getting her emotional DNA scrubbed so she can qualify for work, and I thought about the last time I checked my email at 11 PM because leaving it until morning felt like a competitive disadvantage. Bonello’s film takes place in three timelines—1910, 2014, 2044—where Seydoux keeps meeting the same man and something terrible keeps happening, except the timelines bleed together until you’re not sure which century you’re drowning in. The future looks like an investor pitch deck: clean, pastel, everyone pharmaceutically balanced into placidity because apparently we’ve decided feelings are inefficient and need to be removed. Then Bonello cuts to 1910 Paris and Seydoux is in a mansion waiting for an earthquake that’s definitely coming, and the dread sits on your chest like a weight you can’t shift.

The structure mimics vertigo—you’re never stable, never sure where you are, and that disorientation is the point. Bonello isn’t interested in explaining how we got to 2044 or offering escape routes. He just films what happens when optimization culture reaches its natural conclusion: people volunteering to lobotomize themselves so they can compete. The 2014 section takes place in Los Angeles and I’m not describing it except to say Bonello gets that incel violence and AI futures are the same problem wearing different masks—both are about punishing people for having needs. Seydoux’s face across three centuries tracks the same exhaustion: the exhaustion of wanting things in a world that’s decided wanting is a vulnerability to be eliminated. I adored this film for refusing to pretend we’re headed somewhere we’re not already living. We’re just calling it different names.

bonus: civil war (Alex Garland)

I watched Civil War a few weeks before the election and the woman next to me was on her phone during the scene where journalists get executed in a parking lot. Check your Instagram girlies, the end times can wait. That’s the thing nobody wants to admit about Garland’s film—it’s not showing us some dystopian future, it’s showing us what we’re already doing. We scroll past atrocities between “get your 30-day manifestation challenge pack for $899” carousels. We’ve watched so much violence on our feeds that actual bodies wouldn’t even make us flinch anymore, we’d just wonder if it’s trending or if it’s AI or whatever.

Jesse Plemons in those red sunglasses asking “what kind of American are you?” should be the most overblown moment in the film except it’s the only thing anyone quotes now, which means we all know that’s the question coming. Not if, when. Garland shot this like he was making a documentary about next year and everyone got mad because he wouldn’t tell them which side wears the white hats. There are no white hats. There’s just Kirsten Dunst chasing the shot because what else is there to do when your country’s a crime scene and you’re holding a camera?

The 2020s needed a film that treats American collapse like weather—just something happening around you while you’re trying to get gas. And that, my friends, that’s more terrifying than any lecture about democracy.

2025

bugonia (Yiorgos Lanthimos)

Bugonia is the film that, in my very humble opinion, encapsulates what it really feels like to be alive in the 2020s, which is to say: constantly oscillating between existential dread and the urge to laugh hysterically at the sheer absurdity of everything. While Emma Stone was busy discovering her clitoris in Victorian England in Poor Things, Bugonia was busy dissecting how we’ve become unwitting participants in systems so byzantine and ridiculous that they’d make Kafka weep with recognition. Lanthimos doesn’t just make politics look absurd—he suggests that our real life politics have become so detached from human logic that his clinical framing now reads as documentary realism. I mean, what kind of art are you supposed to create in 2025 when the White House’s own social media is now using SZA’s ‘Cuffing SZN’ SNL song with the caption: ‘WE HEARD IT’S CUFFING SZN. Bad news for criminal illegal aliens. Great news for America.’ to brag about its ICE efforts?

The film serves as a fitting mirror held up to a decade where we’ve watched democracy slowly collapsing in ex-social-media-platforms-now-neonazi-hangout-spots, billionaires shooting cars into space while people die from rationing insulin, and politicians debating whether books should exist while the planet rapidly rises up in temperature. It’s the first film in a while that’s made me snap out of this ridiculous reality for a brief second and unfortunately, that’s the cathartic recognition we may desperately deserve right now.

the sound of falling (Mascha Schilinski)

My mom flinches when cabinet doors close too hard. I didn’t notice it was weird until I was twenty-five and realized I do it too. Her mother did it. I do it. None of us have ever been hit by a cabinet door.

Mascha Schilinski filmed three generations of German women, grandmother to mother to daughter, mapping how a single act of wartime sexual violence ripples forward through decades, showing up in the granddaughter’s panic attacks and the mother’s inability to be touched and the grandmother’s seventy years of silence about 1945. At the same time, the film shows us women folding laundry and making tea and staring out windows and suffering in small ways and in big ways. We see them in these long static shots where nobody moves wrong, and I’m watching like “oh fuck that’s how I move through rooms too”, like I’m trying not to get noticed, and then the grandmother speaks and the daughter cries and nothing gets fixed but something unlocks when you finally see the outline of what you’ve been carrying and understand you didn’t fucking put it there.

Your grandmother did. Because someone put it in her first.

sentimental value (Joachim Trier)

Joachim Trier shot Renate Reinsve and Stellan Skarsgård in an Oslo house and delivered a great film that shows what it looks like when someone tries to turn family pain into art while the family is still alive to watch. Skarsgård plays a washed-up director who wants to cast his estranged daughter as his dead mother—the woman who killed herself when he was a kid—and Reinsve has to decide if letting her father use her to process his trauma is an act of love or just letting herself get exploited again. I watched her demand her married lover fuck her or slap her before going onstage and laughed because that’s what happens when you’ve spent so long mimicking emotions you can’t access them anymore. Me and the rest of the theater are sobbing two hours later because the film understands that some people only know how to love through making art about why they can’t love, which doesn’t make the love less real but it doesn’t make it less painful either.

This is a film that will speak to a lot of Substack culture writers right now—writing essays about their childhoods, posting vulnerable content, turning grief into newsletter subscriptions—asking themselves if making the private public is healing or just another way to avoid actually dealing with it. Trier shot it in a house that’s held three generations of the same unspoken rage and filmed it so you can feel the weight in the walls.

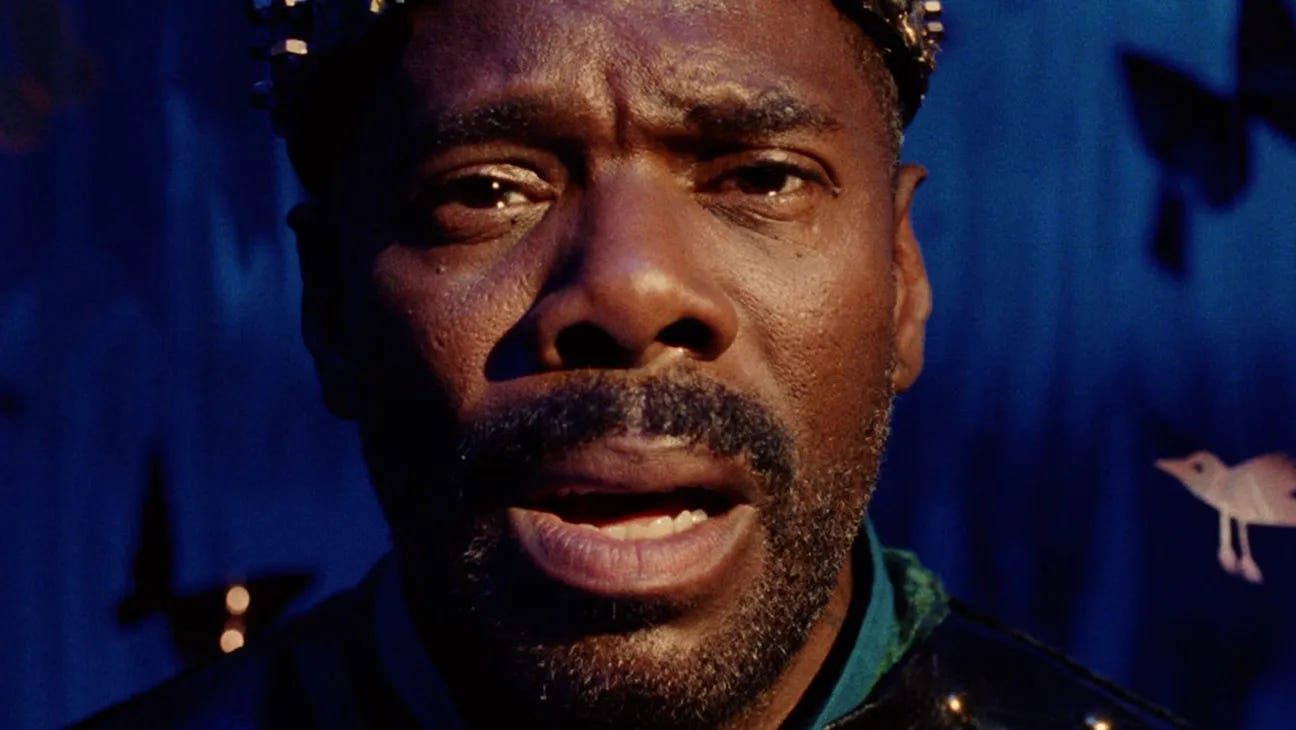

sinners (Ryan Coogler)

Hollywood pretended to care about Black lives for eighteen months after George Floyd’s murder, then immediately returned to casting Black actors as the wisecracking best friend—which makes Ryan Coogler’s Sinners box office success feel like some studio exec finally remembered that yes, Black culture exists beyond trauma for white consumption. Michael B. Jordan plays twin brothers opening a nightclub in 1930s Jim Crow South and when the vampires arrive they’re less metaphor than reality check: monsters have always been here, white supremacy wore fangs long before Bram Stoker, but Black people kept building nightclubs and playing blues anyway. Coogler films the juke joint scenes like they’re the actual point, not historical backdrop or educational content for white audiences—this is Black Southern Gothic as celebration, horror and joy occupying the same frame. The twins want to build something beautiful and the film treats that ambition like it’s normal, like of course you’d try to create joy in a place trying to kill you, because that’s what Black communities have always done.

What stings about watching this in 2025 is remembering how the discourse died the second it required real change, and here’s a film that just exists at the center of its community without asking permission or explaining itself to anyone.

sorry, baby (Eva Victor)

One thing you may have deduced from this list is that yes, I cry in theaters a LOT because I don’t let myself do it anywhere else—lights go down, who gives a beep—so you won’t be shocked when I tell you Sorry Baby turned me into a blubbering mess, but so did everyone around me during that final scene so I can’t be accused of mawkish sentimentality when the entire room was sobbing into their scarves. You’re probably wondering why I’m putting another trauma film on a 2020s essential list—do we really need more trauma porn from this decade—except Sorry Baby isn’t about trauma at all.

Agnes teaches comp at the college where her professor sexually assaulted her because moving costs money and tenure track jobs are rare. She makes dark jokes about killing herself with office supplies and orders the same sandwich every day because bigger decisions feel impossible. Victor treats this not as pathology but as Tuesday.

The 2020s gave us works on sexual assault such as Promising Young Woman (not very good) and I May Destroy You (very good) but Victor sidesteps both approaches. Agnes doesn’t get revenge nor does she get revelation. Three years later she’s still teaching at the same college, still living in the same house, still measuring progress in days she doesn’t want to die. She exists in the years after when everyone expects you to be fine and you’re just trying to remember how to order coffee without dissociating. Victor gets that sometimes healing looks like staying alive until tomorrow. And to top it all off, she wrote, directed, and starred in the film without making it feel like a vanity project.

That’s an essential film in my book.

Want to be featured on That Final Scene and get a free 3-month membership?

I’m always on the hunt for your confessions as part of my Reader Hotline.

You share your most revealing, weird, or controversial takes on films and TV.

I respond and my readers chime in. Think of it as therapy, but I’m not licensed and your thoughts might end up on the internet.

Here’s what I’m looking for:

Plot armor: The show or film that got you through a difficult time.

Spicy take: A controversial film opinion that you’ll defend with your life.

Reality check: The film or show that completely rewired your worldview.

Triggered: When something on screen or in the theater hit you unexpectedly hard.

Send your confessions to sophie@thatfinalscene.com or record your voice message on the link below. Everyone who submits gets the free membership, whether I use your story or not. See you in the confessional.

great list! can't believe we're halfway through the decade. i could say a lot about the understated importance of nickel boys, but i think "Nickel Boys is what American cinema looks like when it stops letting us be safely distant witnesses to its own history" says it all. completely agree with your take on bugonia, too. surreal but surprisingly refreshing—my 2025 period piece.

Great list! Glad to see Challengers get some love, love Luca!