the cinema industry's most dysfunctional relationship needs couples therapy (part 1)

Part 1: Two perspectives on cinema's most complex collaboration.

Sometimes the best conversations happen when you least expect them. And sometimes they happen because your readers are absolute gems who ask exactly the right questions at exactly the right moment.

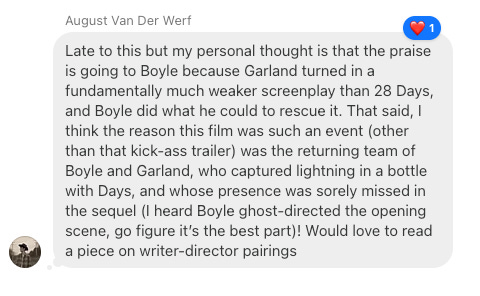

A few weeks ago, August Van Der Werf dropped this message in the TFS Chat about 28 Years Later, questioning whether Danny Boyle deserved all the praise for rescuing what might have been a weaker Alex Garland screenplay. Which led to his ask: "Would love to read a piece on writer-director pairings."

Around this time, Ted Hope also reached out about collaborating on a piece together. Ted needs no intro - he’s basically Substack royalty at this point with his popular newsletter "Hope For Film" being essential reading for anyone who cares about independent cinema innovations, resources & perspectives (see: the NonDē movement). The timing felt ideal. August wanted me to write about creative partnerships, and here was Ted, who's built his entire career on figuring out how to make creative collaboration actually work.

What I thought would be a straightforward conversation about director-producer dynamics became a beautiful back-and-forth about taste, authenticity, and why most people in this industry have no clue what they actually want from their collaborators. And while it’s not exactly the writer-director piece August asked for (that's still coming), his question unlocked something I'd been mulling over: why are creative relationships so consistently dysfunctional, and what would it actually look like to fix them?

And in a perfect bit of timing, I actually met Ted and his wife Vanessa Hope (who’s also a director/producer) in London last Saturday!!!!! Nothing makes a Substack collab feel more real than discovering your internet friends give the same thoughtful and excitable energy in person as they do in their work and writing.

Scroll at the end of this post for the obligatory IRL selfie.

Now let’s dive in ✨

Ted: Sophie, based on your writing, I suspect you to be a fellow "operational improvement obsessive". I am always on the search for the incremental improvements that can advance the product, process, or experience. I think of criticism as a demonstration of appreciation -- if I don't like something I am not going to comment on it. When something or someone has caught my fascination, I want to help make it even better. Not surprisingly, this can create some issues, and I have had to learn to bite my tongue in most situations.

One of the things in the process of cinema that I find needs a good deal of improvement is the director/producer relationship. It is a key spot for collaboration, but I don't even think either really know where to begin. And we don't even think of what we want early enough. So let's start with you. You are going to direct a feature film one day, hopefully soon. I am already looking forward to it ("anticipatory joy!"). What do you want from the director/producer collaboration?

Sophie: Ted, you've identified something that drives me absolutely insane about film discourse: this idea that criticism equals hostility. The opposite is true. When someone spends 3,000 words dissecting why a certain film doesn't quite work, it's because the critic likely adores this director enough to care about their missteps. Indifference gets silence; fascination gets scrutiny.

Your operational improvement obsession resonates with me because cinema is, at its core, a series of systems working in harmony (or failing to). Every great film represents thousands of micro-decisions executed with surgical fidelity. Every mediocre film shows you exactly where those systems broke down.

So when you ask what I want from a director-producer collaboration, I would want a producer who functions as my film's most intelligent adversary.

Not adversary in the destructive sense though. I'm not asking for David O. Selznick sending twenty-page memos about why Jennifer Jones needs more close-ups. I mean adversary in the Socratic tradition: someone whose primary job is to interrogate every choice I'm making until we arrive at something bulletproof. The producer should be the person in the room saying, "I understand why you want this, but convince me it's necessary."

Because most directors are walking around with beautiful, unexamined assumptions about their own work. They fall in love with moments that feel poetic to them but might read as indulgent to an audience. They mistake their personal obsessions for universal truths. A great producer should be calibrated to spot these blind spots before they metastasize into problems that no amount of post-production wizardry can solve.

Look at the Coen Brothers and their relationship with producers like Robert Graf or Tim Bevan. These people are tastemakers who understand that the Coens' best work emerges when their more baroque impulses are channeled rather than simply enabled. When the Coens made The Ladykillers, you can feel the absence of that productive friction. Nobody was there to ask whether this particular homage was worth making.

I would also want someone who speaks fluent film history but doesn't weaponize it. Someone who can reference Tarkovsky's editing rhythms in Stalker not to show off, but because they genuinely believe understanding that temporal architecture might unlock something in our current project. A producer who has seen Jeanne Dielman and Speed with equal seriousness, who understands that both films achieve their respective goals through meticulous attention to pace and space.

More importantly, my dream producer is someone who sees their role as stewardship rather than ownership. Too many producers seem to view themselves as the film's primary author, with the director as their most expensive department head. That dynamic breeds resentment and compromises everyone's best work. The ideal producer understands that their name goes above the title not because they're the creative genesis, but because they're the guardian of conditions that allow that genesis to flourish.

Christine Vachon built her career on this model. When you watch early Todd Haynes or Kimberly Peirce, you can sense an intelligence behind the camera that extends beyond the director—not competing with their vision, but creating the scaffolding that makes ambitious vision possible. Vachon wasn't trying to make Safe more commercial; she was trying to make it more completely itself.

And ultimately, what I'd love in a producer is someone who gets excited about the weird stuff but can also spot when weird crosses over into indulgence. Someone who can tell the difference between a detour that enriches the story and a detour that just shows off how clever I think I am.

But here's where I need to be upfront with you: I'm not really interested in directing anything. The visual language of cinema mostly mystifies me - I see movies as elaborate radio plays with pictures attached. When I watch There Will Be Blood, I'm not thinking about Paul Thomas Anderson's camera movements or the way Robert Elswit lights Daniel Plainview's face. I'm obsessing over how "I'm finished" works as both confession and threat, how those two words carry the weight of the entire film.

This is embarrassing to admit as someone who writes about films and television, but I think in words, not images. Always have. So when I think about director-producer relationships, I'm probably more interested in the equivalent dynamic for television writing rooms or film scripts in development. What does that collaborative push-and-pull look like when you're dealing with story structure instead of shot composition? That’s what intrigues me the most.

Ted: The synthesis of word and image, and then also sound, time, anticipation, and discussion are all different parts of cinema, but cinema is the synthesis of all. I have found most go from word to image to sound and then the other parts too, but I think a non-linear development process can yield some fascinating results.

Years ago I went to a director’s office to discuss a project and he had a long table covered with image pulls for the script. I have known writers who use images as the resting place for their stare as they work. And many speak of using particular music as they write. I have always been fascinated by all that goes into one moment: the past, the hope, the fantasy, the symbolic and the symbolic registry. Personally, I kind of feel unlocked from the time/space continuum in the way I think.

I have grown fond of a development process I use that I refer to as a script interrogation for cinematic potential. I dig in often when my team thinks the script is “ready” and yet it inevitably yields new drafts. We are trying to explore the full potential across all the aspects, including the dialogue with cinema past and future. I think of it as unearthing the “secret languages” – the things that will make different audiences and individuals feel seen and heard, part of the world the film is speaking to.

Sophie: When you encounter directors who seem too eager to work with you, bypassing that important vetting process, do you think they're responding to industry pressure to seem "collaborative," or is it something deeper about how film schools and early career experiences shape directors' understanding of what they should expect from producers?

Ted: I think it's something even more problematic. I think this system we are in turns most relationships into something transactional, and we’ve allowed our creative process to become a product unto itself. Most directors are seeking out a producer who can get their movie made. And they are tuned to think that’s the priority. Most directors think of the producer as the collaborator who is going to take care of the business part of the film – and although that is certainly part of the role, I know I can elevate most projects creatively.

So much of our industry deliberately confuses both the public and the participants as to what a producer does. No one tried to protect the producers’ credit or the definition of the role until recently. The studio’s negotiation team referred to themselves as producers. If producers aren’t thought of to be part of the team that builds the creative vision (as well as the business strategy and plan), they are easier to isolate and alienate.

I’ve never had a director ask me what I want to gain or get out of the project. When they ask me why I want to do it, they seem to be satisfied just to hear why I love the project. Don’t we aim to somehow grow and change with all we do? Isn’t that one of the reasons we engage with things? I know it’s true with me, and I would wonder how my collaborators hope to grow or change by the work we do. I am there to help my collaborators, but I find the best collaborators are also trying to do the same for me.

I find one of the key things that both attract collaborators to me and I get praised for, is my “taste” – but taste is such a complicated thing. I am always refining it. My taste is the “interrogation”; it is the potential of recognizing possibility and the commitment to take things to a new place. Taste is not stable.

I am wondering how you define taste, Sophie?

Sophie: Funny you should ask that, because I've spent these past few weeks hovering over this exact term—in fact, I just published the piece "taste matters but can you afford it?" exploring how taste functions as cultural capital, but I realize I never actually stopped to think about what the word means etymologically. To me it just comes naturally, which is probably why I never interrogated it properly.

"Taste" is one of those words where the English version never quite captures what I'm actually thinking. In Greek, we have "γούστο" (gousto), borrowed from Italian, which is closer to aesthetic preference or style. But there's also "γεύση" (gefsi), which is more about the act of experiencing or sampling something—literally tasting, but also metaphorically testing the waters of an idea or feeling. And then there's "αίσθηση" (esthisi), which connects to sensation and feeling, the root of "aesthetic."

When I think about taste in the artistic sense, I'm unconsciously cycling through all three concepts. The English word suggests you've arrived somewhere, collected your static opinions about Mozart and Antonioni. But what I actually mean is more like my grandmother's soup: this ongoing process of sampling, adjusting, developing better methods for recognizing quality even when it looks nothing like what you expected.

So taste, the way I understand it, is pattern recognition married to cultural intuition. It's the ability to spot authenticity even when it's disguised as something unfamiliar. And crucially, it’s the difference between someone who makes films and someone who makes "filmmaker" their entire personality on Instagram.

Which brings me to what you're describing with directors and producers, and I have to ask—how many producers actually have this kind of gefsi? Because what you're talking about with script interrogation, this ability to sense when something is almost there versus just competently executed, that's incredibly rare. Many producers I would assume treat taste like having accumulated the right opinions about established hierarchies. They can tell you why certain films worked commercially, but can they feel when a script is reaching toward something that doesn't have a precedent yet?

The dynamic you're describing requires a producer who's willing to be wrong, to have their own assumptions interrogated alongside the director's. And frankly, I suspect that level of intellectual vulnerability might be even harder to find than directors who understand what they actually want from the collaboration.

Ted: I love “the ability to spot authenticity even when it's disguised as something unfamiliar”, and you are right to say that most producers lack gefsi. They do! I think that is why I became disillusioned with my producer class, first while at Amazon and later back in the field. It shouldn’t be surprising that most are in it for the transaction and not the art. Most producers want to make something audiences love so that they make money.They don’t care if the film advances the form, culture, conversation, or community. You are helping me to better recognize that is all that I care about. Thanks.

To me I think taste is the fascination of the complexity of everything. When I see or hear or experience anything, my mind, body, and heart are racing in all directions, looking for connections to the past, present, and what may one day come. And I love that. Just thinking about it makes my eyes water. Some of that has come by deep effort and training, but there’s also just that I find it incredibly enjoyable. It is always a realm of deep unknown and vulnerability. Certain works just send me reeling and the truth is in the moment I can’t fully fathom it. And then in the act of considering some is lost and some is out of reach, but for me taste is the appreciation of that complexity and the willingness to consider it.

I’ve made my living based on my taste, and my son is now doing it to, albeit in a much different field. I think we can be far better trained to develop this awareness of what all people, objects, and experiences spark – but we have to cultivate it far better than we do. From what you’ve written that I’ve read, I see an alignment in this hope that we all can.

Part 2 of this conversation will continue over at Ted’s newsletter so make sure you subscribe to read the rest:

Till then…your Substack besties xoxo 🤳

A final note for people with taste 🫦

While the internet's prioritizing hot takes and SEO-optimized nothingness, I’m here building a sanctuary for people who believe film and television criticism can be thoughtful, accessible and fun all at once.

For the price of a truly mediocre sandwich, consider joining the resistance with a paid subscription – it keeps independent film writing alive and the algorithms at bay.

Plus, you'll get exclusive access to After Credits, my monthly handpicked selection of films & tv shows that will stop you from doomscrolling Netflix AND exclusive access to my more personal reflections.

Now go forth and raise those standards, darling.

- Sophie x

Inspiring conversation- Thank you!

Oh my gosh, I was on a set when this was published and I totally missed it until now! Thank you so much for the shout-out and for this piece! I’m so flattered and honored to have helped inspire such a stimulating and insightful conversation between you and Ted!!! 😊😊😊